In this article, we examine what the reader of this article is doing.

A number of means and principles intervened in the reading of this text. We can roughly classify them as follows:

Electronic device, paper or similar material

Delimited shapes on the material that constitute the area of the text

Sequences of time and space

Turkish as a language

A language world unique to the writer and the reader

Let us now briefly examine them.

The electronic device (phone, tablet, computer) is, at first glance, the place where this text is read. The text exists within the container of this device, and not outside it. That is to say, it is not present, for example, in the hand that holds the device, or on the table on which the device rests, and so on. In more ancient times, it would probably have been a book or a piece of paper, or leather, wood, or even clay or stone. These places, by preserving what is engraved on them with a suitable medium, to the extent of their own capabilities, ensure permanence. Without permanence, it is impossible for writing to exist in a place. In this respect, we can characterize these places as places that provide permanence according to their possibilities.

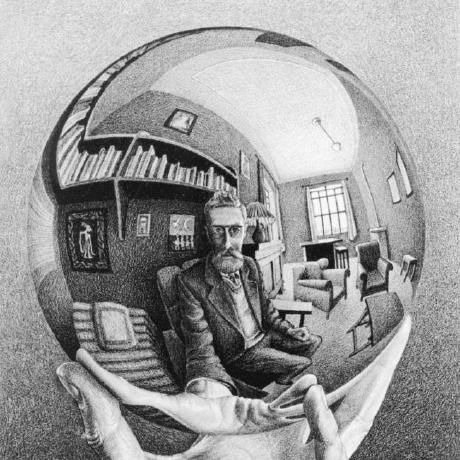

However, writing is not located everywhere in this space, but in a certain part of it. This certain part of the space is the space for writing. This space occupies a place in the space. In this respect, this space has an interior. The reader of the text looks both at the space and at the area of the text in the space. For example, if the text is in the middle area of the screen, the reader looks at the middle area to read the text, and if it is at the bottom, he looks at the bottom. However, what makes it possible for this area, for example the middle area, to be an area is the space that surrounds it. In other words, the reader has to look at both the space (the electronic screen) and the writing area in the space (the middle area of the screen). Otherwise he cannot see the writing.

What is actually looked at in the space on the screen are the shapes we call letters and punctuation marks. Just as the space is inside the screen, these shapes are also inside the space. In other words, just like the screen, the field also has an interior. Whoever looks at the shapes here is also looking at the field and the screen. Thus we understand that the reader is now looking at three things both separately and at the same time: The screen as space, the shapes as letters, and the space on the screen occupied by these shapes. Otherwise he cannot see this writing.

There are other aspects that make it possible for the reader to read this text. These are the sequences. The shapes we call letters and punctuation marks are arranged in a certain order. In current Turkish spelling, this arrangement is from left to right. But what is meant by alignment is more than that. In Turkish or any other language, we can arrange letters and words from left to right, right to left, up and down, but none of these arrangements could have come about without the possibility of arranging things one after the other and side by side. Arranging things one after the other and side by side is a more fundamental category that also makes it possible to arrange things in this direction or that direction. This category is not derived from the act of arranging in this direction or that direction. For example, if we write the word “apple” as “amle” in the opposite direction, and ask the reader to read this sign to find a word that makes sense from right to left rather than from left to right, he can read “apple” in the same way, but what the reader is actually arranging in both directions is primarily “back-to-back” and “side-by-side”. “e-l-m-a” is next to each other, and “a-m-l-e” is next to each other; and each of them is consecutive in the relation of priority and posteriority. What is present in each of these directional sequences is succession and juxtaposition. The reader does not arrange them from left to right without first arranging them side by side and consecutively. However, in a simpler sense, including the directional sequence, we can say that in order to read the text here, the reader looks at the “sequence”. So, in a broad sense, sequence is one of the essentials of reading this text. Without the sequence, this article cannot be read.

But interestingly, the sequence is neither on the screen, nor in the writing space, nor in the figures. The reader cannot read an article here without arranging time one after the other and space one after the other in a way that is unique to the reader.

This sequencing, which is unique to the reader, cannot be imposed on the reader by this screen, this space and these shapes. If the reader does not already have the ability to align, he cannot read this article. How will he follow the letters and words if he has no sequencing ability? How will he perceive one before and the other after? We think that even these simple examples are enough to understand that this sequencing feature does not originate from sensation and the perceived world. The reader has a time of his own, and this time does not come to him from these forms, nor from the outside world at large.

However, it cannot be said that the reader has read this article only because he or she looks at these three things and has the ability to arrange them in his or her own way. This writing is more than these three things, and that is why there is something else in the things that it brings to the typesetting. On a nakedly blank screen, this writing does not exist. On a part of the screen other than the space dedicated to this text, this text does not exist. This text does not exist without the shapes inside the space on the screen. However, this text does not exist in terms of the shapes themselves. This writing exists through a language seen through these shapes. This language is Turkish. A person who knows Turkish somehow gives meaning to the shapes arranged here.

Now we need to proceed a little more carefully. We have identified the location of the shapes as the space on the screen and the location of the space as the screen. In this way, we have said that the place of the shapes in the text is the screen. Then we linked the ability to read these shapes and the spaces in which they are located to the sequence in them. The space of the sequence was the reader himself. Now we understand that in order to read the writing here, a language is required. We call this language Turkish. So, where is Turkish? For example, on the screen? If it is on the screen, if we broke the screen and destroyed it, Turkish would also disappear. Obviously, the place of Turkish is not the screen and its contents. Turkish is neither on the screen, nor in the shapes, nor in the typesetting. The person reading this article does not look at Turkish by looking at the screen and its contents. However, one who does not look at Turkish cannot read this article. In other words, one who does not speak Turkish cannot have read this article. Turkish is being looked at on this screen, but neither the screen nor its contents are Turkish. These are not the place of this language. Turkish, as a language, is in another space. And now, the person looking at this screen, while reading this article, is connected to that space, the space of Turkish. This is what is happening. The situation of Turkish is similar to the situation in the sequence. Turkish cannot be obtained from the perceived world. Turkish does not exist in the external world. The place of Turkish is the Turks. What is meant by the name Turk here is identity. The essence of the concept of identity is neither this screen, nor what is on it, nor the outside world. The outside world includes the “genetic structure”. In other words, the genetic structure is not the location of a language. Language is not formed on the basis of genetic structure, nor is identity formed on the basis of genetic structure. What makes it possible to read this article is what transcends the genetic structure. On the basis of genetic structure alone, this article is essentially unreadable.

However, there are things in this article that go beyond Turkish as a language. Turkish is a language among languages. Since this article is of course written in accordance with the language and spelling features of Turkish, it is the writing of a language. However, these language and spelling features, although not taken from the outside world, are something that the reader acquires later. What is meant by “afterwards” here is the idea of “after language”. The reader of this article is essentially “in the language” and in terms of this language, “in the language as Turkish”.

One who does not have a language cannot read this article. The “language” here is prior to Turkish. Without this “language”, a person could not exist in the Turkish language either. In other words, to “exist” in Turkish is first to “exist as a language”. We understand this from this:

What makes it possible to read this writing are the letters, syllables, words and sentences in this writing. The writing consists of sentences. Therefore, we find the essence of writing as a sentence in the first hand. Then we turn and look at the sentence, and the sentence is made up of words. We realize that the essence of writing is words. When we look at words, we see that words are composed of syllables and letters. However, we cannot give independent meanings to syllables and letters. The smallest meaningful unit we have is words. If “meaning” were not in question, we would of course have to go all the way back to syllables and letters. Because words are made up of them. But “meaning” stops us at words. So if we ask what and where is the “meaning” in the word, of course we cannot rely on the screen and other things. The place of “meaning” here, if we look at the above, is first and foremost in Turkish. In Turkish, words have meanings. But in Turkish we cannot (for the time being) give syllables and letters independent meanings. Of course, we do not give individual meanings to words either, words only make sense when a sentence is completed. But the smallest meaningful element in a sentence is not syllables and letters, but words.

Even if the smallest meaningful element is a word, we find the meaning itself in the sentence. So, for example, the words “en, element, word, meaningful, we find” are meaningful on their own, but it is the sentence composed of these words that reads the meaning. In this article, the reader reads the word in the sentence. That is, he looks at the words based on the sentence, but not by looking at the words in isolation. In other words, the sentence is in the view as the basis of the “unity” of the words. But, let us say it again, what is looked at in the sentence, that is, what is looked at in the landscape, are the “words”.

And words are, essentially, either the subject or the predicate. In this respect, it is the subject and the predicate that are looked at in the sentence.

Now, neither the subject nor the predicate can be obtained from the outside world as a conception, nor can they be obtained from Turkish as an acquired language. Turkish cannot ascribe the categories of “subject” and “predicate” to a person. If the person does not have these, he cannot learn Turkish anyway. The categories of subject and predicate and the sentence that brings them together must exist before Turkish. Otherwise, even if the person somehow knows Turkish, he cannot read this article.

We understand that what must be present before learning Turkish is a comprehension of subject, predicate and their combination. Unless this comprehension is present before learning Turkish or any other language, one cannot read this article. This pre-existing comprehension is “language”. In this respect, language is the basis that makes Turkish possible. This language, needless to say, is transcendent to the genetic structure; moreover, it is transcendent to the culture of Turkish or any other similar language. Even if all cultures come together, they cannot automatically attribute to a person an active “subject” and a “predicate”. The only things that can be predicated are their analogs, and the analog can only exist if it is somehow based on a principle somewhere. Therefore, what is meant by “cannot be predicated” is “cannot be essentially given”. We are not going into the analytics of the matter.

Now let us ask about the place of language in the above sense. Let us remind you right here: The place of a thing is the basis of its existence. Therefore, if the place of something is to be found, it is important to remember that if the place to be found disappears, the thing in that place must also disappear. In other words, finding the place of something is not an easy thing. However, as of this writing, the march so far should have already foretold the present results.

Let us ask again, what is the space of language in the above sense. Let’s see. Is it the screen? Obviously not. If we destroy the screen, language will not disappear. Is it the relations inside the screen? These are not either. Is it our ability to string? How can it be? Who types? That’s not it either. Let’s say it is Turkish. But we cannot. We have already found language above by proving that language precedes Turkish. So, where is language?

Wherever language is, it is clear that it is neither in space, nor in time, nor in those who relate to it in order to exist. But it is equally clear that the actual space of this writing is not the screen, nor the space within it, nor the shapes, nor the syntax, nor the structure of a language, nor the outside world, nor anything like these. This writing is, essentially, in language.

The author of this article is able to write based on language, and as such, based on the Turkish language. The reader of this article can also read it on the basis of language, and as such, on the basis of the Turkish language. In other words, the place of the author and the reader of this article is the same place.

In other words, the author and the reader are the same person in this writing. Otherwise, this writing cannot be (really) read.

This concludes our examination of what the reader of this article does.