Research suggests that words are not strictly necessary for reasoning.

Humans have been expressing their thoughts in language for tens (perhaps hundreds) of thousands of years. This is a distinctive feature of our species. So much so that scientists once suggested that the capacity for language is the main difference between us and other animals. And as long as we can talk about these thoughts, we are curious about each other’s thoughts.

- The number of people over the age of 100 is expected to exceed one million by 2030

- World population projected to increase by 20-30 percent by 2050

- Biden wants to bring Israel and Saudi Arabia together

“A question like ‘What’s your thought?’ is, I think, as old as humanity,” says Russell Hurlburt, a research psychologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. But how do scientists study the relationship between thought and language? And is it possible to think without words?

According to decades of research, the answer is a surprising ‘yes’. Hurlburt’s work, for example, showed that some people don’t have an internal monologue. This means they are not talking to themselves in their heads. And other research shows that people don’t use the language regions of their brains when working on nonverbal logic problems.

For decades, however, scientists thought the answer was no – that intelligent thinking was intrinsic to our ability to form sentences.

“One prominent claim is that language fundamentally allows us to think more complex thoughts,” says Evelina Fedorenko, a neuroscientist and researcher at MIT’s McGovern Institute. Scientific American reports that this idea was championed in the mid-20th century by legendary linguists such as Noam Chomsky and Jerry Fodor, but has fallen out of favor in recent years.

New evidence has prompted researchers to reconsider their old assumptions about how we think and the role language plays in this process.

“Unsymbolized thinking” is a type of cognitive process that takes place without the use of words. Hurlburt and a colleague coined the term in 2008 in the journal Consciousness and Cognition, after decades of research to confirm that it was a real phenomenon.

Studying language and cognition is a really difficult subject to describe and notoriously difficult to study. “People use the same words to describe very different internal experiences,” says Hurlburt. For example, someone might use similar words to describe a visual thought about a parade of pink elephants as they use to describe their non-visual, pink elephant-centered internal monologue.

Another issue is that language-independent thought can be difficult to recognize in the first place. “Most people don’t know they are engaging in non-symbolized thought,” says Hurlburt, “even people who often do.

And because people are so trapped in their own thoughts and have no direct access to the minds of others, it can be tempting to assume that the thought processes going on inside our own heads are universal.

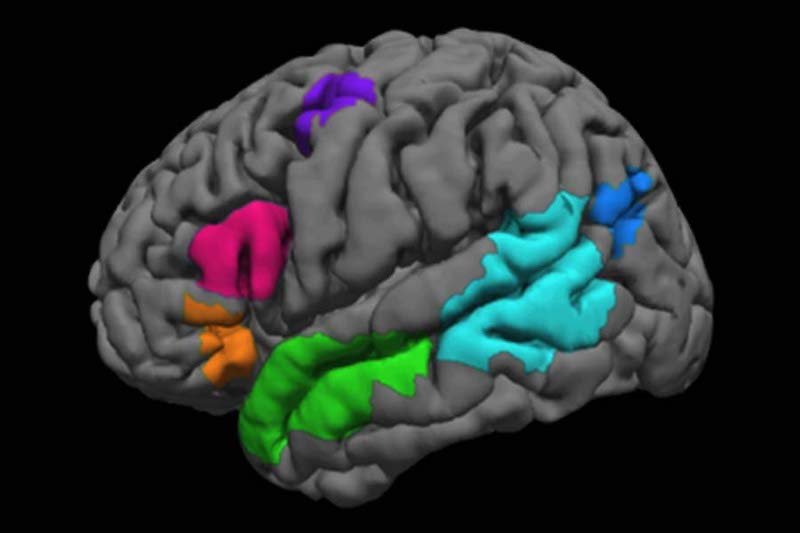

However, some labs, like Fedorenko’s, are developing better ways to observe and measure the connection between language and thought. Modern technologies such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and microscopy give researchers a pretty good picture of which parts of the human brain correspond to different functions; for example, scientists now know that the cerebellum controls balance and posture, while the occipital lobe performs most visual processing. And within these broader lobes, neuroscientists have been able to predict and map more specific functional regions associated with things like long-term memory, spatial reasoning and speech.

Fedorenko’s research takes such brain maps into account and adds an active component.

“If language is critical for reasoning, then there must be some overlap in neural resources when you are engaged in reasoning,” Fedorenko hypothesizes. In other words, if language is necessary for thinking, then when someone uses logic to solve a problem, brain regions associated with language processing should be engaged.

To test this claim, he and his team conducted a study in which they gave participants a wordless logic problem to solve, such as a sudoku puzzle or some algebra. The researchers then scanned their brains using an fMRI machine while they solved the puzzle. The researchers found that the language-related areas of the participants’ brains were not working when they were solving the problems. In other words, they were reasoning without words.

Research such as that by Fedorenko, Hurlburt and others suggests that language is not essential for human cognition, a finding that is particularly important for understanding certain neurological conditions such as aphasia (loss of speech). “You can sort of eliminate the language system and a lot of reasoning can work just fine,” Fedorenko said. But that doesn’t mean it wouldn’t be easier with language.”

Live Science. June 19, 2022.