The color of water is the color of its container.

Junayd

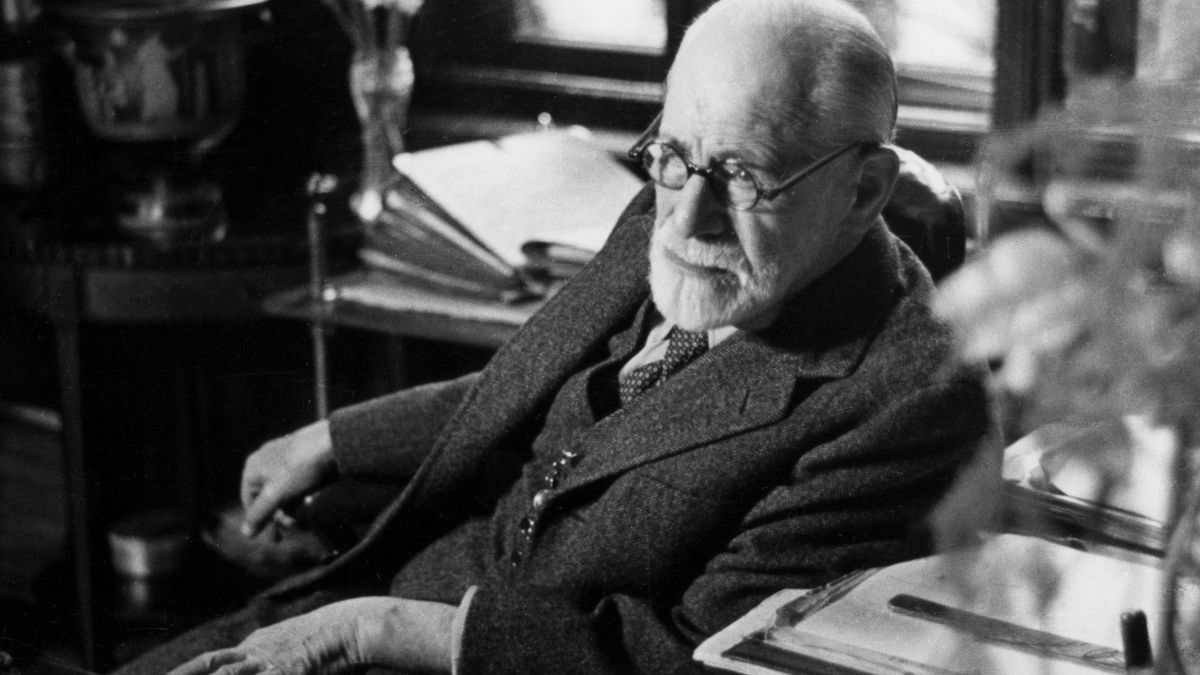

Psychoanalysts and philosophers have addressed the issue of sexuality in different contexts in recent centuries, leaving the world with many issues to discuss. Among these, Freud’s accounts have undoubtedly attracted the most attention and had the most significant impact.

Freud’s views on sexual life going back to childhood was one of the most controversial. However, these views caused a strong curiosity as well as a reaction. Thus, from a much earlier period, the issue of sexuality was positioned as the basis that determines one’s identity, and human beings, human societies, living life, culture and history began to be reinterpreted accordingly.

With Freud’s initiative, the undocumented “pre-history” of the human being began to be elucidated in this respect. This latter point means unraveling another aspect, which is as important as identifying one’s individual identity, namely social identity, through sexuality.

Leaving aside the evaluation of its points of departure and its results, this approach is undoubtedly quite comprehensive and therefore close to perfection.

In the first aspect, unpacking individual identity is important in terms of determining what burdens the individual has taken on in his/her journey from his/her specific starting points, what he/she has become, and then what his/her destination is.

In terms of the second aspect, this individual identity is important in terms of what it is in terms of its social ties, and then what the individual identity of the “society”, which is like one big individual, is in similar terms.

The most important difference of the Freudian approach to the second aspect, i.e. the unpacking of social identity, is the aforementioned context of “prehistory”. Because according to this approach, the social events experienced in terms of “pre-history” take place in the individual identity of the individual in some way; and they “affect” the post-pre-history of the human being both individually and socially.

In this respect, the opening up of the “pre-history” constitutes a basis for opening up the individual and society with the same importance and on the same basis.

These are the aspects we mean by comprehensiveness. However, in order to bring this comprehensiveness closer to perfection or to make it perfect, what is important is what “binds” the before and after in terms of both the individual and society.

According to Freud, it is the concepts of “psyche” and “consciousness” that bind the “before” and “after” of history in the individual and society. These are the elements that bring the work closer to perfection.

In terms of putting forward these contexts, Freud wants to make both individual and social identities in the world we now live in “scientific” by opening and connecting them within a systematic framework. As a result, he calls the field that provides such scientificity “psychoanalysis”.

What distinguishes and distinguishes psychoanalysis from many psyche theories is that it opens identity as a topography on the basis of “psyche”.

In the articles “The Dawning of Jahiliyya”, we said that topography is the most important scientific principle. It is necessary to see what is meant here from this perspective.

Freud’s opening up of identity on the basis of topography and his comprehensive approach and the astonishing results he achieved have been subjected to a lot of criticism from various circles and disciplines and have been almost ignored today.

We have prepared the following short article to show that many of these criticisms do not even touch Freud’s essentials, and that the issues in question must go even further than Freud thought.

This article will be expanded in much greater detail at a later date.

Sexuality is a matter of “unity” and “completion” and “disunity” and “incompleteness”, that is, “incompleteness”.

Unity is something broader that also encompasses sexuality. Unity is not itself a concept that can be grounded in opposition. Unity precedes even the “idea of unity”.

Understanding “unity” also depends on getting rid of the “idea of unity”; this is what is meant. At this point, “understanding” does not mean “thinking, perceiving”. In order to understand such a thing, one has to be in it. Such a person knows it by itself.

But it is necessary to see that sexuality is within the scope of unity and, moreover, is an example that can show it in its own measure.

Completeness, similar to “oneness”, is something that has to be understood from within. It is also a concept with which we need to think about the concept of “sufficiency”.

Disjunction, in terms of the concepts of unity and completion, requires thinking of disjunction. Incompleteness, similarly, must be thought in terms of “incompletion”.

An examination of how these two things happen reveals that the disjointed and the incomplete are disjointed and incomplete due to a change of basis and ground, that is, their grounds have changed.

After the separation and deficiency are completed due to the change of ground, it is understood that the separated and the incomplete can no longer constitute unity and completeness in terms of merging and gathering, because for the separated and the incomplete, salvation from this situation depends on the transformation of the ground.

For the disjointed becomes disjointed by changing the ground; the incomplete becomes incomplete because the ground has changed.

At this point, it is understood that it is the ground that is essentially discrete and incomplete.

Therefore, the ground of discrete and incomplete is different from the ground of unity and perfection; discrete and incomplete cannot attain unity and perfection without changing the ground, in this sense.

But the issue begins in the orientation of the discrete and the incomplete. The discrete and incomplete can tend towards “unification” and “gathering” instead of changing ground in order to get rid of their discrete and incomplete state. As a result of this orientation, the separate and incomplete falls into the way of “touching” other things.

Eating, traveling, looking, tasting, touching, learning, teaching, reforming, preaching, speaking, observing, leadership, management, entrepreneurship, branding, occupation, revolution, and many other similar jobs are just “images” that the one who falls on this path takes on.

In a more general sense, this imagined path is actually “sexual indulgence”; in essence, it is about being “separate” and “incomplete”.

This is not the case for the one(s) who are “in Oneness” and “complete”, as we mentioned in the previous article using sexual intercourse as an example.

Without attaining unity and perfection, neither the discrete nor the incomplete can find tranquility. Since they cannot find tranquility, they are in a state of “constant arousal” and run to unite and gather in some way, but without “touching” the “ground” of the matter.

Of course, there are some points where we can identify these issues within the visible life, that is, within the known universe. But it is necessary to correctly identify where to start from. The correct identification of these points is done through the person himself. That is, through the “individual”.

A more careful person might think of “object (thing)” in a broader sense instead of the word “individual” here. In this case, the issue becomes much broader. In this case, the possibilities of addressing the issue from the point of view of “nature” also begin to emerge.

The points where the differentiation through the individual begins in visible life and the known universe are birth into the world and development from the mother or something that can replace the mother. In this context, the first place where the individual differentiates is the mother. Therefore, the first event where “unity” is “disrupted” in visible life is “birth from the mother”.

Therefore, an approach that does not address the issue from this point or a similar point cannot be considered inclusive and careful.

Similarly, lack corresponds to the time after separation from the mother in the “visible (ma’lûm) universe”; the “individual in the mother” does not need the outside like the individual outside. The “outside” that the “individual in the mother needs” is the “mother” itself.

Separation and incompleteness begins with birth from the mother, in terms of what is born. After this separation, the individual falls into need in a broad sense, and with the emergence of need, into striving for its fulfillment. The world thus becomes a place of striving and commodity for the one after birth.

The ones who fulfill the need in the above sense for the one who comes into the world are the mother and father, or the “educators” or “governesses” who replace them; in the broad sense of educating, i.e. “rab’lik”.

The fact that human beings, in their own unique “history”, have given birth to offspring that are in many respects much more needy than the offspring of other living beings is very important in this respect. However, we do not go into this very important issue.

It is also significant that the essence of the father in the mother, i.e. his “place in the biological composition”, as seen in the world after birth, is as “the giver of the seed of the individual to the bearer of the individual”. However, the implications of this point will not be sufficiently examined without elaborating on the principles of the “father” in terms of the “cognition of the individual” in a broad sense.

At this stage, the mother and father are the world itself for the newborn. And in the later stages of life, the world continues to be the world itself, always as a mother and a father, in different displacements.

The mother and father, who fulfill the needs of the individual in a broad sense, are therefore also the world to which the individual feels pleasure and appetite.

Similarly, for the individual in the world, mother and father are also the world to which law, aspiration, love, imagination, hatred, friendship, enmity, and so on are directed and in which they are experienced.

In addition, the individual has to remember the mother and the father in every object to which he is oriented throughout his life. For example, a boy looks for his mother as a wife throughout his life; a girl looks for her father as a wife. The inversions of this are similar here. Even in the case of things to hate and be hostile to, there are the memories and fixations of life with the mother and father behind the scenes.

In this context, the life of the separate individual goes on from mother and father to mother and father, with mother and father, closed in on itself.

The issue of sexuality, therefore, begins in childhood and continues in the world that opens up to the child, in the life that is formed in visible life. We will go into the details of this and Freud’s mistakes in this regard in later articles.

Because of the reoccurrence of this closed circle in every child who comes into the world, social life and all institutionalized structures are composed of the conflicting and disguised patterns of this circle and are reproduced each time with their own inner core. These institutions are, for example, law, politics, economics, science, art, philosophy and religion.

If one looks carefully at these institutions, there are traces of the relationship between the separate individual, mother and father.

Prior to the separation of the individual from the mother in visible life, the birth of the individual into the womb and what is born determines the guiding principles of the pattern that will emerge after birth.

This is the point that limits the nature of the Freudian approach and in fact starts the matter from a “deeper” level than even his imagination could reach. It is precisely what will be determined at this point that will determine the extension of psychoanalysis and how it will be transcended.

At this point, Yalçın Koç is the name that opens the door that allows for expansion and transcendence.

In this context, it should be noted that the fundamental difference between Freud and Yalçın Koç is the difference between “Moses Man” and “Moses Prophet”.

The difference between “Moses Man” and “Moses Prophet” comes from the difference between “das Es (It)” and “Hüve (It)” on the basis of the Name, transcending “a language”.

The difference between “Moses Adam” and “Prophet Moses” comes, in another respect, from the difference between “Egypt” in terms of “the place of Moses Adam” and “Anatolia” in terms of “the place of Prophet Moses”.

This difference is a difference about the essence of the “mother-born individual”; it is therefore the difference between the denial and the affirmation of the “places” related to the “heart” in the topography of the individual.

What is meant by denial here is not an intellectual attitude; it is more than that; it is partly experiential.

The denial here is also the denial of the “love” inherent in the “heart” through the force of eros, which is thought to be inherent in “it (das Es)”. In other words, it is the lovelessness of Freud’s “Moses Man” and therefore the “Freud Man”.

This “lovelessness” is only seen in Anatolia.

Because Anatolia is the home of “Love”; it is visible and audible in every inch of soil, in every singing bird, in every rugged mountain…

We can see this difference from an intellectual point of view by looking at the issue of what is born in the womb in terms of its “framework”; again, we do not have the space to go into the details of the theories and names mentioned in this article; in fact, what we want to tell through this series of articles will be through things that are more visible, audible, livable, after the frameworks on which they are based are made clear. However, we don’t want to go into such a narrative without drawing attention to the theoretical frameworks.

According to Freud, the psyche that is born is das Es (it) and is the somatic motor system; that is, the neurological body. “das Es” is composed of inner forces. These forces are eros and thanatos, eros being the forces of love and thanatos being the forces of destruction.

das Es(o), by coming into the world and being influenced by the external world, forms “das Ich” and “das Über-Ich”. Accordingly, the threefold topography of the psyche is completed; and from this topography, consciousnesses are differentiated, dynamically ensuring unity that is unique to the individual. The essential in this topography is das Es; the other two regions come from das Es, for das Es comes by birth, from the father and mother, biologically and in the womb, self-formed by its own intrinsic powers.

Those familiar with the Theologia Ir-Rationalis will see that Freud’s conceptual connections here cannot be theoretically justified. As we have said, we will deal with these points more extensively elsewhere.

Freud’s conception of the psyche as a triadic topography, based on the pronouns “He, I and super-me”, is based on the fact that Freud takes language as a basis. The idea of language as a basis together with the idea of topography and the linking of these two conceptions to the psyche are among the aspects that make Freud distinguished. This distinction is a distinction not only for psychologists or psyche theorists, but also for the philosophers and priests of the West, right after Plato, Plato of Attica.

In terms of the triadic topography, das Es, born of the mother and the father, is essential, and this is composed of inner forces. Freud’s identification of the born individual in terms of forces coincides with the development of new ideas about “energy” and “force” in physics in his time. The pictures of energy and force as the essence of the physical realm should have supported the idea that the individual who comes as a motor system could also be composed of forces. However, it should not be overlooked that Freud’s conceptions of the psyche were essentially based on the analysis of the psyche. Freud unravels the psyche through dream analysis, personal psyche analysis, analysis for those in need, and readings of mythology; and as mentioned very briefly above, he builds a very broad and comprehensive theory on this, based on language and topography. According to Freud, comprehending these theories and “psychoanalysis”, the science at the center of these theories, cannot be achieved without resorting to personal analysis and dream analysis. For those who do not go down such paths, psychoanalytic theories may seem worthless and absurd. But for those who do engage in analysis, this is not the case at all.

Taking language as the basis (arkhe) is one of the most powerful aspects of this theory. By taking language as the basis here, we mean taking the pronouns “it, I and super-me” as the regions of psyche and qualities of consciousness. Anyone who wonders why taking these pronouns as the basis strengthens the theory can quickly grasp the issue by turning inward and looking at what he or she is pointing to with the pronouns “it and I” and what the descriptions the theory gives of these pronouns correspond to in these places. But an assessment of what the theoretical structure is, of course, requires more than this.

Freud said that what the human species had established on earth was narcissism, and that this was shaken by two scientific facts. One of these is that Copernicus showed that the earth is not at the center of the universe and Darwin showed that human beings were formed on the basis of evolution. Thus, humanity was shaken in terms of the idea of centrality and unique superiority it attributed to itself. However, it was the discoverers of the unconscious and the psychoanalysts who dealt the lion’s share of the blows. Through the scientific discovery of the unconscious, it was shown that what human beings call “das Ich (the I)” is driven by another region that is not under the control of this region, and human narcissism came to ruin. Freud says so.

It is worth investigating here whether showing that “das Ich (the I)” is not a region not under the control of human beings themselves is an essentially new result in terms of the conclusion that human beings are slaves to another life in terms of the “fatalistic understanding” in the Greek-Latin-Church realm.

Fate, that is, the question of whether human beings are guided by something else or not, is the greatest curiosity and the saddest pain of all human cultures, because the most important issue for human beings, deep down, is whether they are free or not. Similar problems apply to Plato, the greatest thinker of this realm. For Plato, too, the existence of the individual unfolds subject to mechanisms that are somehow conditioned to “necessity”.

These question marks about Plato and Freud are more obvious for Aristotle, Kant and the like. Both Aristotle’s individual and Kant’s individual are prisoners of ideas, and in a much harsher and more desperate way. In the articles on “The Making of the World”, we briefly pointed out this point in the context of “continuity”. In the same articles, we also described Spinoza’s individual, this time in terms of “anthropomorphism” on the basis of the mind (mens). The situation of those in the contemporary world under the guidance of these thinkers can be compared accordingly.

For Plato, the psyche, even more so than for Freud, is created. The created psyche is in a knowledge and state of its own. After its creation, the psyche is enslaved to the world and thus to soma, that is, to the body. In this respect, what is meant by the cave is soma, that is, the body. Plato’s effort is to bring the psyche, which is enslaved to soma, back to the state it was in before soma. In this sense, it is the “Logos” that provides the exit.

The context of psukhe’s creation and its connection to the idea of Theos brings along a mechanism of “necessity”. In terms of this mechanism, the extent to which human beings are free or not must be evaluated from this point of view.

At the moment, it does not seem possible to say that the Greco-Latin-Church realm has overcome this issue by eliminating some religious and spiritual images from the discourse and making some methodological changes, let alone overcome it. The current view of “science” and “technology” does not present a different picture from its predecessors in terms of whether the individual is free and whether the universe in which he or she lives is nothing more than a machine. For example, studies that go to great lengths to argue that the individual is subject to a genetic mechanism ultimately lead to nothing but the conclusion that the individual was determined before his or her conception and that he or she has no ability or way out of this determination. Examples of this conclusion abound in physics, biology, history, philosophy and other fields of endeavor. The realm of the Greco-Latin-Church seems not to stop considering it a success and progress to frame the individual on the basis of a neurological diagnosis of the somatic individual, and, by correcting chronological events through partial experience, to subject the life of the individual and the environment at large to a kind of secular fate and bondage. Therefore, neither in the past nor in the current state of this realm, seeking any remedy for what the individual himself is and how he can be free is nothing but a futile endeavor, a waste of time.

What the individual is and how he or she is free should be sought in Anatolia. Because this Anatolian land, even in its last phase, did not refrain from declaring this to the world by saying “I was born free, I live free”. In Anatolia, the greatest answers to the questions of what is a human being and what is the world are given by being engraved directly into the heart. Here, when asked “where did you come from”, they say “I came from dem, I have come now”. If asked what you have come for, “I have come to make hearts”. Thus they open the door of freedom to every hearer. This is how they are. “They”, in Anatolia, once they take a glance, they turn their origin from being a mere bone to a jewel.

Having briefly completed Freud’s conception of the individual who is “not born free” and “cannot live free” from these perspectives, let us look at what Yalçın Koç has to say.

As mentioned above, the issue of the individual depends on the conception of the birth of the individual. One cannot talk about a conception of the individual without talking about birth and, in this sense, the beginning. No one, whether explicitly or implicitly, can think of an individual without envisioning a birth and a beginning specific to the individual. Therefore, we must first look at Yalçın Koç’s conception of the birth of the individual.

According to Yalçın Koç, the research into the birth of the psyche is an archeo-graphia of the psyche. In other words, it is the writing of the initial principles of psukhe. Without a psukhe archaeo-graphia, the study of psukhe-logia, i.e. the study of psukhe-physics, is incomplete. Incompleteness in this sense is not a simple deficiency; this incompleteness means leaving the matter in limbo on the ground. Therefore, studies on this basis cannot be considered a science of psukhe in any sense. The arheographia of psukhe depends on a “scientific” unraveling of the origin(s) and stages of psukhe. By “scientific” here we mean, broadly speaking, the theoretical conception of psukhe. Therefore, a study in this direction should be carried out with the theory and the theoretical idea.

On the basis of psukhe, the theoretical intellectuality examines the elements that the individual performs and possesses inherent to his or her birth, and then examines his or her state of affairs in terms of the stages through which he or she passes, thus framing the ultimate boundaries of theory and intellectuality. No intellectuality is outside the scope of this framework. If it is understood that what is meant by intellectuality is the whole of the activity of thinking and perceiving on the basis of language, which includes philosophy, science and theology, one can immediately see how wide a field this issue concerns.

Without understanding the nature of intellectuality, the judgments of things determined on the basis of intellectuality cannot be finalized. The nature of intellectuality is determined by opening the ground of intellectuality. In this sense, the ground is the theory. Therefore, intellectualism cannot assert anything that is not in the theory as a “fact” as long as it rests on its own ground. Otherwise, it violates its own ground. And the one who violates his own ground is disqualified from judgment. The situation in which intellectuality does not rest on its own ground means the transformation of intellectuality, which means the transformation of the intellectual. In this case, it is unnecessary to talk about intellectualism.

However, it is very difficult to unpack what theory is and what principles it contains from within intellectuality. Because intellectuality is not theory and the ground of intellectuality is theory itself. Therefore, intellectualism has to be of a different nature from its ground. Therefore, the nature of intellectuality is not suitable for opening the theory itself.

However, it is necessary to open the theory from within intellectuality in order to see the limits of intellectuality.

Since these two conditions are valid at the same time, the opening of the theoretical from the intellectual is a difficult matter. It requires “mastery” and “knowledge” to handle such a difficult issue.

Yalçın Koç achieves the opening of theory in intellectuality through “intellectuality about theory”. He grounds his theoretical intellectualism in many different aspects. Central to this grounding is the activity of “mimetike poiesis, that is, imitative construction”; in essence, the “architectonics of language”. In other words, it constitutes theory imitatively in intellectuality, in a way that pushes the boundaries of intellectuality and on the basis of the architectonics of language.

We will discuss the power of this method and the expansion it enables at another time.

The architectonics of language is the basis of theoretical thought. One cannot understand what language is and what the individual in language is subject to without thinking architectonically in terms of language.

Arkhitektonik is composed of the words “arkhe” and “tekton”, which means “initial principles”. Arkhitektonik is also translated as “architecture” and arkhitekton as “architect”. However, Yalçın Koç specifically states that the nature of his work should not be expressed as “architecture”.

Even understanding the reason for this is enough to understand the importance of what is being done in these texts. Let’s not go into that either.

In terms of the architectonic idea, the language of the individual is divided into “language as organon (instrument)” and “language as arkhe (essential)”. The original language is the language that the individual is born with; and from this language the individual falls and comes to language as an organon, and on this basis to ideas, and finally to “a language”. Accordingly, the theoretical is the natural, i.e. innate, language of the individual, and the languages that the individual falls into are under the record of this language, but in a way that is “closed” in terms of the fallen language.

The infant who has just come into the world forms language on the basis of psukhe. This formed language is innate. The infant is itself constituted psyche, that is, constituted (poiesis) psyche; and it constitutes language for itself on the basis of its internal topography, that is, on the basis of its “internal spelling”; the constituted language is the “form” of the born psyche, that is, of the constituted psyche. Yalçın Koç refers to this formally constituted psukhe as “as’kın”.

The concept of ascendent, in terms of the theoretical idea, is the opposite of the “fallen” as an individual on the basis of language.

Transcendent, as briefly mentioned above, is the psyche that comes by being born, whereas the imagination, as the “fallen transcendent”, is the fallen psyche, and its form is language; the performance of this form is “ideology”.

Here we do not touch on many points that need to be explained and illustrated in detail. We are just trying to highlight some concepts as best we can so that the relevant aspects of our topic are a little clearer.

According to Yalçın Koç, the “transcendent” is the psyche that is not under the registration of the motor system, evolution, and the body at large; there is no “external world” for the “transcendent”. For the “transcendental” is born as a “world” on the basis of its internal topography, under the registration of its own theory.

It should be noted that evolution, genetics, the brain, and the body based on them cannot in any way be the basis for the ideas of “one” and “unity”; they cannot encompass these concepts and the things that are based on these concepts.

However, it should not be assumed that the theoretical thought and the “transcendental” is based solely on this impossibility. Since we do not go into detail here, we do not elaborate on these points.

Moreover, the unraveling of the meaning of evolution, genetics and the brain for man, and the achievement of their science on a large scale, depends on putting the theory on a pedestal. To expect that the ultimate framing of these issues can be achieved with the current scientific understandings is a mere illusion and a delusion.

Again, the psyche as transcendent is not under the register of the above things and there is no external world for it. Transcendent, subject to unity, is itself “a world” and has come by genesis.

This psyche undergoes two falls. In its first fall, the one world begins to differentiate into an “inner world” and an “outer world”. The object viewed in terms of the inner world and the perception of the outer world become different.

Yalçın Koç says that the baby probably cries because of this first fall; that is, because of the decomposition of the “one world”.

As of this first fall, the language the baby falls into is “exhibition as language”, and what it is actually watching is “painting”.

However, we can go into this in detail and make theoretical analyses of archaeological findings, art, rhetoric, some religious cultures, neurological issues, logical problems and many psychological problems. Let us point this out.

After the first fall, the infant goes through another fall, thus completing the distinction between the “inner world” and the “outer world”. As of this fall, the individual is “fallen”, and it is at this point that he or she begins to “learn” from his or her environment, essentially by losing what he or she was born with. In this sense, “developed (adults)” are also “fallen”; that is, they are psukhe that have fallen from the language that comes with birth; by undergoing an internal-external differentiation.

The form of the imaginary is “language”. The imagination moves on the basis of language, depending on the body under the registration of the motor system.

The difference between Coach and Freud is clear at this point.

According to Freud, the psyche that is born, das Es, is biological. According to Koç, the psyche that is born is not biological in this sense, but being “alive”, it is also the basis of the biological. We do not touch on the subtle issues in this regard. But be warned, it should not be treated in analogy with the “spirit” teachings encountered in many different realms. It is necessary to take what a person says as he says it.

A thinker who opens the theory in intellectualism cannot be lumped in with intellectualists or theoreticians of doctrines who do not know what they are talking about. This kind of cheap way of doing things is reserved for those who are incapable of thinking even in intellectualism, and there are many examples. More importantly, it can sometimes be an escape route for intellectuals who are looking for a way to suppress the theory. One can understand this by looking at oneself.

Yalçın Koç identifies the born psyche as beyond the beginning in the separation of language and body. This psyche is in its own body by forming its own language. Yalçın Koç calls this constituted language “the theogonia of constituted language”; the idea of “the theogonia of constituted language” is also the area in which Plato’s idea of psyche and theory is transcended.

The born psukhe and the transcended are not the same thing in this respect. The arising psyche is the constituted psyche that comes by birth; the transcendent is its own language, as the self-form of this psyche. This distinction is important to note.

Transcendence, in this sense, is “a world”.

This is an important point that helps to understand what is beyond even Freud’s imagination.

The constitutive psyche is the formal and substantive name that comes by birth; this name essentially describes and constitutes nouns and pronouns for itself. In fact, this is the constitutive aspect of the theogonia of composed language.

In terms of these nouns and pronouns, the transcendent is “He (Hüve)”, “I (ene)” and “You (ente)”. pronouns on the basis of the nouns substituted by these pronouns.

These names are the constituted psukhe as the “original name”, the constituted it (huwa) as the first name, and the constituted I (ene) as the ultimate name. The original noun is internal to the simple landscape that arises through the simple forces that constitute the psukhe, i.e., the constituted psukhe; it is through the “course” of this noun that the image of “it (huwa)” is formed, on the basis of tab; the image of “it (huwa)” is the original pronoun. That which is formed, as that (huwa) formed by being struck, is born on the basis of the simple landscape; as struck. With the description of this noun, the pronoun “I (ene)” is formed, on the basis of tab. The name “I (ene)”, which is formed by being formed, is born, darbî.

Thus, the first concepts are completed for the baby, namely he (huwa) and I (ene).

“You (ente)” The pronoun comes from the compound “I (ene)”; that is, it substitutes the noun “I (ene)”.

The concepts of tab, darb and substitution need to be read extensively in the relevant texts; however, since they are closely related to our topic, we would like to exemplify these concepts in the sequence of the article and show the application of the theoretical structure to these issues.

The psukhe, born as described above, has completed its peculiar forces by forming a language for itself; this language is composed on the basis of nouns and pronouns and is in cognition.

Accordingly, Ash’kın’s consciousness is beyond Freud’s conception of consciousness.

In fact, Freud’s main shortcoming at this point is the “noun”; his main mistake is that he has narrowed the topography.

The fact that the pronoun should only be dealt with on the basis of the noun is what necessarily expands the theoretical structure of this subject.

The fact that “it (huwa)” on the basis of the noun is “before the I” is also important in terms of the issue of “huwiyyat”.

If “I (ene)” were to be prior to “I”, the “I” would be the moon of the psukhe that is born; in this case, the question of what the identity of this “I” is would arise. If the identity of the “I” were to be “the psukhe itself” by virtue of being the same as the psukhe that is born, the psukhe itself would enter into the course through the “I”, in which case memory would also be open to the course, in other words, the idea of memory and the idea of substance would be canceled if such a sequence were to be considered.

Neither the individual nor the human being can be talked about by canceling the idea of memory and substance.

Therefore, it is not possible to prioritize the “I” for the born.

It is also possible to think of putting the “you” first for the “I”; in this case, the psyche of the born should be depicted on the basis of the “you”, essentially like a governess.

To assess whether such an idea would result in narrowing the topography, it needs to be examined more broadly.

The fact that He is prior to the thou is in the estimation of a wide range of “human” people, including Ibn ‘Arab’i. In fact, we would like to examine this and other issues from the point of view of human beings in the “The Dawah of Jahiliyya” articles, in order to criticize their understanding of Islamic History.

As a result of what has been said above, Ash’kın itself possesses the aforementioned nouns and pronouns, even before it falls. The “fallen ash’kın”, on the other hand, possesses the pronouns in itself under the registration of the ash’kın it has lost.

Love and “falling love, that is, the fallen” are “unity” on the basis of language architectonics.

In this framework, what is separated from the mother is the as’kın, which has names and pronouns before the fall, and is not under the registration of the soma; the state of the as’kın in the womb is “blurred” in terms of the dream’kün, from the first conception, i.e. fertilization, to the fall’üş, i.e. the establishment of perception, including perception. Because of this blurriness, there is no trace of the cognition specific to love in the dream. However, this period is preserved in the memory and is under the record of the unity of languages on the basis of language architectonics.

Here, we do not touch upon the fact that love and the constituted psukhe, which is the basis of love, are not “psukhe itself”. For such a framework is sufficient to show the difference between the theoretical and theoretical understanding of psyche and the Freudian understanding.

This difference also applies to other psyche theories and Plato’s cosmogony.

In the present situation, no psyche theorist can encompass Yalçın Koç’s theoretical thought, neither in its essence, nor in its principles, nor in its subtle connections. This is true not only for psukhe theorists, but also for scientists, philosophers and theologians in a broad sense.

The widening of the theoretical intellectual framework opens up new avenues for the application of the issues of psychoanalysis and, more importantly, removes a major obstacle to “freedom” by showing that the existing (discrete) individual is not bound by these either.

Due to space limitations, we would like to briefly apply this framework to the issue of sexuality to show how it can be extended.