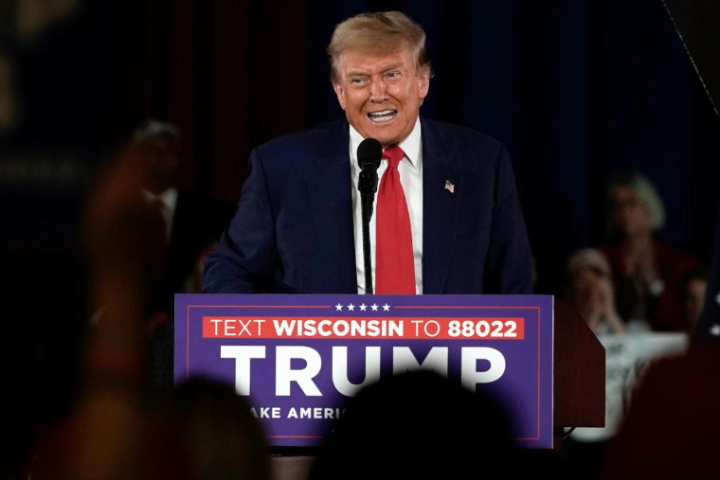

Shooting deaths, the storming of the Capitol, out-of-time rulings by the conservative-dominated Supreme Court: In the United States, conflicts are coming to an unexpected head. Historian Manfred Berg sees the country as closer to civil war than at any time since the War of Secession. At stake are ethnic identity and white nationalism, hegemony and lifestyles, fears and autocracy. A key role is played by former President Donald Trump.

ntv.de: Mr. Berg, at least since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, the U.S. has been going through a social fracture that seems to have no end. What has he done to democracy?

Manfred Berg: The worst thing was that he successfully undermined the basic norm of a peaceful democratic transfer of power: That the loser of an election accepts the result. Political scientists in the U.S. call this the loser’s consent. A clear majority of Republican supporters still believe the lie of the stolen election. A significant portion even sees storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021, as a legitimate form of protest. Through the work of the investigative committee, we have already learned many details about how far-reaching Trump was in his not particularly well-coordinated, yet very determined, intentions to nullify this election through some kind of coup.

What happens when there is no longer a loser’s consent?

Historians and social scientists see this as a precursor to civil war. There is a great precedent in U.S. history, the Civil War of 1861 to 1865, which was triggered by the presidential election of 1860, when the South did not accept Abraham Lincoln’s election and used it as a cause for secession.

- Educating the body’s army: How your immune system learns to distinguish between good and bad

- Burberry, Richemont Shares Drop Due to China Uncertainties and Weak US

- The Manhattan Project, the world’s first nuclear weapons test ve Widows of Village

In the U.S., it is very often said that the strength of the democratic system is that it can renew itself, toward a more perfect union. Was there another comparable situation after the War of Secession, from which there was then a way out? Or is the United States in a historically unique position?

At the very least, I would argue that such a dangerous, aggravated, polarized, and violent situation has not existed since the War of Secession. There has always been political violence at the individual state level. But such a sharpened polarization between two identity-based political camps that see each other as a mortal threat to their core values and conceptions of life, I would say, has not existed like this since the American Civil War.

What are these different conceptions of life aligned with?

It has to do with demographic-ethnic polarization, which is central to understanding American politics. About 90 percent of the Republicans’ supporters are white. Among Democrats, they are now only a minority. We have a clear polarization of the party system – all studies, all polls show this – in that the Republicans are the party of the white, conservative, traditional, religious, rural milieus, and the Democrats form a very broad coalition of social and ethnic minorities and the liberal, relatively well-off whites on the other side. This is reflected in social spatial separation. There is the famous contrast between the coasts and flyover country, but above all enormous conflicts between urban and rural areas. For the Republicans, demographic development was and is a huge problem.

Neither side feels well represented in this conflict. Trust in institutions-only 7 percent trust Congress, 14 percent trust the judiciary-is at record lows. Why is that?

After World War II, the U.S. was considered the epitome of a consensus-oriented civic culture. Because of its famous checks and balances, the U.S. Constitution has always been seen as a very stabilizing force. Stability, however, presupposes a willingness to cooperate and bipartisanship. If they are removed, this system, which offers an enormous number of opportunities for deadlock, becomes dysfunctional. Among other things, because rural states are significantly overrepresented in Congress. In addition, for the past ten or fifteen years or so, there have been obvious attempts to make it at least more difficult for minorities in the individual states to exercise their right to vote, by means of manipulative and discriminatory election laws.

The Republicans did not always have this anti-democratic tendency as they do now.

There have always been forces in the Republican Party that have said we have to open up, we have to tap into new groups of voters. It was no coincidence that George W. Bush and John McCain were successful in wooing Hispanics. Donald Trump, on the other hand, with the slogan “Make America Great Again,” has basically promised the restoration of a Euro-American white hegemony and has led the party on a radically xenophobic and racist course. The Republicans formed an entirely new alliance after the civil rights movement to become a rallying point for conservative white Christians, especially evangelical ones. The liberal wing of the Republican Party, which had always existed, was marginalized. But all of this was not necessarily politics that could be called anti-democratic or dangerous to democracy; it was the basis of the Reagan coalition, and it was very successful. It won large majorities in elections in the 1980s.

And today?

Today, I see more of a great parallel to the pre-Civil War period in the 19th century. Back then, it was the slaveholding class that felt threatened, that believed their power and their way of life were mortally threatened and that they had to defend themselves. Then, too, it was more of an identity conflict than one involving material distribution issues. It’s similar today. I see the demographic transformation of the United States as a very important factor. In the 1960 census, or even as recently as 1970, almost 90 percent of the population classified themselves as white, and a good 10 percent as African American. In 2020, it was still about 60 percent white, but nearly 19 percent Hispanics as the largest minority, more than 13 percent blacks, and 6 percent Asians. For several years now, more than 50 percent of children born in the United States have been nonwhite. According to U.S. projections, by about 2045, white Americans will be only the strongest ethnic minority. This change is accompanied by an enormous sense of threat in parts of the white population, fears of foreign infiltration and loss of hegemony. These developments are driving polarization on a massive scale.

You had mentioned the civil war. According to international conflict researchers, there are two decisive factors that can also be observed in the USA. First, the Republicans as a party are grouping around an ethnic identity, and second, the democratic institutions have been weakened. From a scholarly perspective, is the U.S. closer to civil war than at any time since the War of Secession?

Yes, unfortunately, it is. When the norm of democratic power transition is undermined, when potential electoral defeat is seen as a fundamental threat in these polarized identity camps, political violence is an option. Cultural imprints also come into play here; a strong state is more likely to be perceived as a threat to freedom in the U.S. than in Europe. Citizens claim the right to bear arms in order to defend themselves against a tyrannical state if the worst comes to the worst. If the self-evident features of democratic institutions are then no longer accepted and there is this strong polarization between identity-political camps that stalk each other, that is dangerous.

What role does Barack Obama’s presidency play in this development?

For a considerable part of the white population, Obama’s election was a narcissistic mortification of the first order. Without him, Donald Trump would be inconceivable as a counter-model, as the leader and standard-bearer of a counter-mobilization of white nationalism. However, Trump’s 2016 election victory was not inevitable. Hillary Clinton lost to Trump because she campaigned poorly, presented herself as representing an aloof liberal elite uninterested in the hardships of ordinary people.

So the two camps are churning?

There have always been phases and reversals in U.S. history where it’s clear that one side has now more or less gained the upper hand. Take the election of 1932, which ushered in the era of the New Deal and a long period of dominant liberalism. Then conservative hegemony began no later than 1980 with Ronald Reagan. Today, these camps, their respective constituencies and strongholds are roughly equal. The result is a fight by hook or crook, a “winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing” to shift the balance to one side or the other. The fight over the Supreme Court and its political instrumentalization is also a very worrying sign. An institution that is supposed to have a peacemaking function is becoming a political pawn. However, there have been long phases before when conservatives were extremely dissatisfied with the Supreme Court and then came up with the plan: We have to take back the Supreme Court. That has now been achieved.

There have been multiple identity-motivated deaths, assassination plots against Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, the storming of Congress on January 6, 2021. At what point can you say, yes, this is a civil war?

When you talk about civil war in the context of American history, you have certain very strong images in mind, namely the War of Secession. That is a war that cost 700,000 people their lives and was fought by regular uniformed armies and professional militaries. That’s not how we should imagine it nowadays. Much more typical is what political scientists call low intensity conflict, that is, a high, ever-increasing level of political violence. Some hate crimes are motivated by the so-called Great Replacement Theory (the supposedly purposeful replacement of the white population, ed.). This is not new; think of the horrific attack in Oklahoma City in 1995. Those were right-wing terrorists. Therefore, one could argue that the U.S. is in a low-intensity civil war. This kind of permanent violence, of terrorism, and also the increasing willingness to legitimize violence as a means of politics, exacerbates the situation. Consider Trump’s 2017 call, “Proud Boys, stand back and stand by!” directed at a far-right militia. The events of January 6, 2021, this is becoming increasingly clear, were a violent coup attempt initiated by Trump. All of this taken together, I would define as a civil war-like situation. And the culmination points where the potential for violence shows up are always contested elections.

So the tensions could erupt around the congressional elections on Nov. 8?

Presumably, Republicans will capture a majority in the House of Representatives. Then the president and Congress will be hostile to each other. In the past, the partisan division of power between Congress and the president was not a problem. Eisenhower governed with a Democratic Congress most of the time. Nixon governed with a Democratic Congress. Reagan governed with a Democratic Congress. But then bipartisanship was still part of the U.S. political culture. Now we have polarized camps that have been deadlocked for many years. The signs are not good. Almost 40 percent of Republican and Democratic supporters think that dividing the country into red and blue states (Republicans and Democrats, editor’s note) is not a bad idea at all.

And if another Democrat wins in 2024, Republicans could feel even more cornered. Add to that climate change impacts and possibly refugee movements from Central America the likes of which the U.S. has never seen. So, if the ethnic issue is central, the situation could become even more acute.

The idea that all it takes is the right president to reconcile the country is simply naïve. The U.S. is already too divided for that. Joe Biden was also only a compromise candidate. It will be similar in the November elections. At the moment, many problems are coming together, and they are multiplying. The American lifestyle, which we share in many respects, is also reaching its limits. California has a population of 50 million. That’s almost as many as in the major Western European states, but almost without water. And yet we live a lifestyle in which the inhabitants of Los Angeles use more water per capita than Germans. And in our country, it rains even more. The environmental catastrophes will be added to this in the future.

All this sounds almost apocalyptic.

Unfortunately, we have experienced some things in recent years and months that many people thought were completely alarmist. As a historian, one tries to explain in retrospect why events that were not in the horizon of possibility for contemporaries for a long time then came to pass. We are the contemporaries of our own present and must also deal with the supposedly impossible. Twelve or fifteen years ago, especially after the election of Barack Obama, I was rather optimistic about the future of the United States and thought that this was a sign that the old conflicts were receding into the background and that there could be a new social consensus in a multi-ethnic society. That has come to nothing. The polarization has continued.

Roland Peters spoke with Dr. Manfred Berg / Source: NTV.de