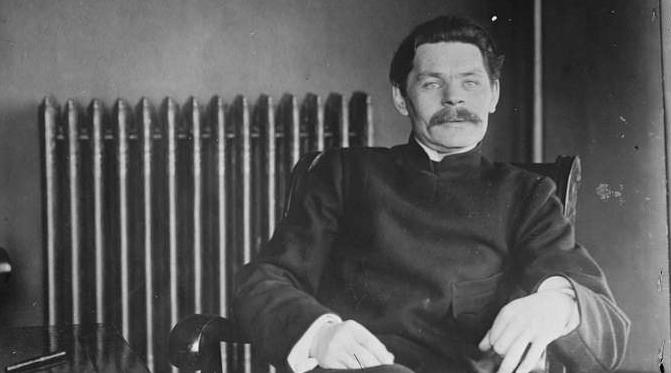

In the past, in Soviet culture, Maksim Gorky‘s portrait hung next to Lenin, almost as a symbol. In addition to being the first great Russian writer to emerge from the proletariat, Gorky was also known as a close friend of the Bolsheviks and was considered a pioneer of Socialist Realism. Behind this icon, however, there was another Gorky, unknown to the Soviet public. This Gorky, who was hidden from the public, was not an ordinary person, he was almost a holy figure, and eulogies were written about him. But with the opening of the Soviet archives, it became clear that Gorky was actually a much more complex and tragic figure than he appeared. It has long been known in the West that Gorky was also a journalist and that his voluminous correspondence was in the archives. This correspondence showed that Gorky was not really a Bolshevik at all. After 1917, he had serious doubts about the methods of the revolution and was therefore sent into exile in 1921. He returned from exile in 1928, but he was never a true supporter of Stalin, on the contrary, he was one of his prisoners, even one of his victims.

Lenin and Gorky met for the first time in 1902. This thirty-four-year-old writer, known as Alexei Peskov, quickly made a name for himself and gained a prominent position in the Marxist intellectual circles of St. Petersburg in the mid-1890s. The first qualified writer to emerge from the city’s underworld, Gorky was the first to vividly depict this world. The working class could easily identify with Gorky’s stories because they reflected their daily lives and conveyed their rebellious spirit. While Gorky used the income from his writings to finance the Social Democrats, his relationship with the Bolshevik wing of the party, especially its leader, was not always stable.

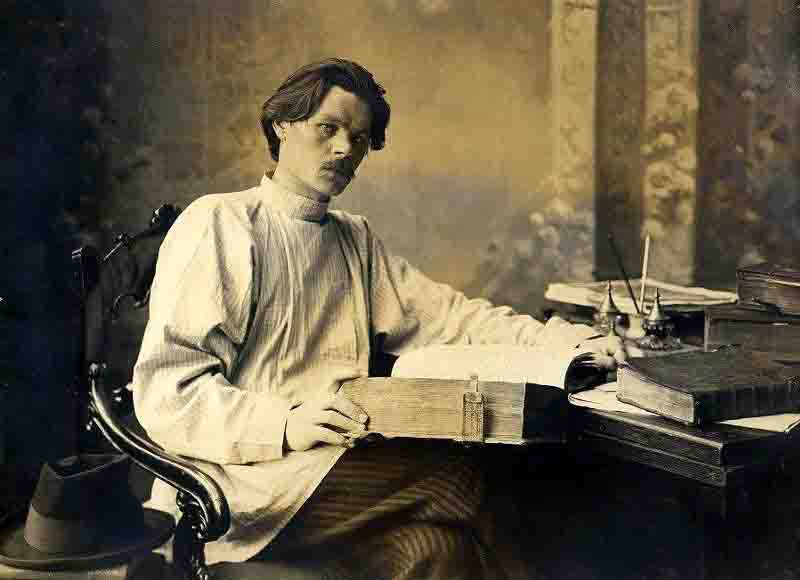

Like many other intellectuals, Gorky’s passion for revolution was based on a romantic and idealistic outlook. For him, revolution meant a great struggle of the human spirit for freedom, brotherhood and spiritual growth. He took a fundamentally humanist approach and therefore never accepted the strict discipline or dogmatism of the Bolsheviks. He even once told the famous painter Repin that he was glad that he did not belong to any party, because for him it represented freedom and he thought that humanity needed this freedom.

While Gorky admired Lenin as an intelligent, charismatic leader, he disliked his attempt to confine vital differences to abstract theories. Between 1909 and 1910, while teaching workers at Lenin’s house on the island of Capri, he had disagreements with him and with Bogdanov and Lunarcharsky, the leading cultural theorists of the Social Democratic Party. According to Lenin, workers could only succeed with disciplined cadres within the party, but could not become an independent cultural force. Gorky and other educators, however, saw the cultural and spiritual progress of the working class as the driving force of the revolution.

Gorky had harsh debates with the Bolsheviks in 1917 as he focused more on the civilizing mission of the revolution. He even accused them of inciting the violence of the February Revolution. At a time when a great wave of anger and rage against the tsarist regime was unleashed, crowds attacked prisons, courts and police stations. Gorky’s home was very close to the sites of the clashes in Petrograd and he witnessed these events. Between 1917 and 1918, he wrote many articles criticizing the events in the independent socialist newspaper Novaya Jizny. In his view, there was no trace of cultural progress or spiritual maturity in the spread of violence, the rise of anti-Semitism or the royal pornography that emerged after the fall of the Tsarist regime. Gorky denied that a social revolution had taken place and thought that what people called a “revolution” was a series of violence triggered by “zoological instincts” and an ancient outburst of rage aimed at destroying Russia’s civilizational layer.

Gorky’s pessimism was based on his literary rejection of violence. He judged the revolution on its own humanist ideals and refused to be molded by the circumstances of the time. Russian intellectuals, however, saw the violence and destruction as the natural reaction of a people oppressed for decades and justified the conflicts with the long-term goals of the revolution. Some even argued that what had happened to old Russia was an exorcism and that a new and more just world would emerge from its destruction.

But Gorky’s response to such praise is clear: a shovel is always a shovel. As he said in his courageous speech on the anniversary of the February Revolution, never before published anywhere, “A revolution can be revolutionary only when it is a natural and firm expression of the creative power of the peoples. The release of the instincts that people have accumulated under slavery or oppression does not constitute a revolution. It is only a revolt of hatred and resentment; it does not change our lives, it only leads to suffering and relentless evil. A year has passed, and can we now say that our people are better, kinder, smarter and more honest? Of course not. Not one of us can say such a thing. We still live with the meaningless traditions, prejudices, stupidity and misery of the monarchy. The greed and evil inculcated by the old regime are still in us: a people who still cheat each other and rob each other at the slightest opportunity, and bureaucrats who both bribe the people and insult the people.”

Gorky’s heartfelt words were directed at the intellectual class, which he saw as a civilizing force in the revolution. During the civil war, he used his connections with the Bolsheviks to save many intellectuals from persecution. He transformed the former home of the merchant Yelisev into a writers’ refuge in Petrograd and set up his own publishing house to reprint Russian classics. This publishing house was not only a business, but also a charity, and it helped many people – Gorky, translators, editors, writers, journalists, academics, musicians and artists – to survive. Such prominent figures of 20th century Russian literature as Zamyatin, Gumilev, Babel, Chukovsky, Khodasevich, Mandelstam, Blok and Zoshchenko owed their survival in difficult times to Gorky’s patronage.

Gorky’s table was always home to an interesting and colorful company: writers, artists, workers and sailors, including names like Shaliapin, who condemned the Bolsheviks, as well as Bolshevik leaders Lunacharsky and Krasin, and even a former duke, Gavril Konstantinovich Romanov.

Anti-Bolshevik intellectuals thought that Gorky was being hypocritical. According to them, Gorky pretended to be the defender of the people and the intelligentsia, while at the same time supporting the Bolsheviks who oppressed them. However, the reality was very different from these claims. Gorky used his privileged position within the regime to mitigate the Bolsheviks’ harsh policies and save as many intellectuals as possible. He could not have done these things if he had clashed with the regime from the very beginning.

By 1921, however, this delicate balance had become almost impossible to maintain. The methods used by the Bolsheviks in suppressing the Kronstadt sailors’ mutiny clearly demonstrated their cruel dictatorship, which even their most loyal followers protested against. Meanwhile, the Red Terror continued unabated, culminating in the show trial of the Social Revolutionary Party. In Petrograd, the city’s leading intellectuals were arrested and Gorky was placed under surveillance. The deaths of Russia’s two greatest poets, Blok and Gumilev, completely changed Gorky’s relationship with the Bolsheviks. For Blok, who was supposed to go to Finland for treatment, was prevented from traveling by Zinoviev, the Party’s Petrograd official, while Gumilev was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka and shot without trial for his alleged involvement in a monarchist conspiracy.

But the final straw for Gorky was the new regime’s insensitivity to the famine crisis. The Bolsheviks’ excessive grain confiscation led to millions of people living in the Volga-Ural region facing starvation. Unable to find a solution, the regime allowed Gorky and a few others to appeal to the West for help. However, the fact that the aid came from an American organization led to the arrest of other prominent figures, if not Gorky. Gorky was forced to leave the country, partly at Lenin’s urging. Lenin was ostensibly concerned for his health, but the real reason was probably his discomfort with his criticism of the government. Gorky was therefore in fact the first in a series of dissident writers forced into exile by the Soviet regime.

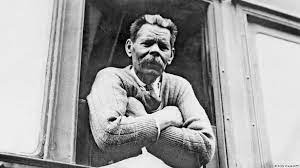

Exile was torture for Gorky. He could not bear to live either in Russia or abroad. On the one hand he missed his own country, on the other he felt too tired and weary to return to Russia. After setting out from Berlin and wandering restlessly through the spa towns of Germany and Czechoslovakia, he finally settled in Sorrento, Italy.

What kept him in exile throughout the 1920s was not the nature of the Soviet regime, but the Bolsheviks’ hostile attitude towards art and their rapprochement with the peasant class under the New Economic Policy. Although he had always opposed the rise of the Bolshevik dictatorship, he was firmly wedded to the idea that in order to legitimize it he had to rein in the instinctive anarchism of the peasantry. However, the arguments he used to rationalize this aspect of the Soviet regime were strengthened, especially after Lenin’s death.

“Yes, my dear friend,” he began in a letter to the French writer Romain Rolland, “Lenin’s death was a very heavy blow for me. I loved him. I loved him with rage.” The writer Nina Berberova, who knew Gorky when he lived in Berlin and Marienbad, described the effect of Lenin’s death on Gorky: “He was filled with regret,” she said: “He reevaluated everything that had happened up to then, the October Revolution, the early years of Bolshevism and Lenin’s role. In the end, he came to the conclusion that Lenin was right and that he was wrong. Because at that time he was convinced that Lenin’s death had orphaned not only himself but the whole of Russia.”

What convinced him to return home was old-fashioned Russian nationalism. First of all, he could not tolerate Russian emigrants – and they could not tolerate him. The more anti-Soviet the emigrants were, the more pro-Soviet Gorky was, and he did not hesitate for a moment to react. Moreover, the fascist movement was gaining strength in Italy, and the Eurocentric conception of civilization that underpinned Gorky’s arguments against the Bolsheviks was deeply shaken. Growing disillusionment led him to glorify Soviet Russia as a morally superior system. He returned to Russia in 1928 and settled permanently in 1932. The Kremlin honored the writer by turning his return into a propaganda campaign. But the regime to which Gorky returned was at that time in deep conflict. On the one side were Stalin’s policies of collectivization and industrialization, and on the other were critics of these policies, such as Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky.

Initially, Gorky tried to stand in the middle between the two sides and tried to balance the power. For him, Stalin’s strict policies were the only way to save Russia from its backward peasant past. But he disliked him as a person and was particularly opposed to his attitude towards art. From 1928 to 1932, he both supported him, albeit superficially, and reined in his extreme policies. In fact, this was similar to the game he had played with Lenin between 1917 and 1921, whereby dozens of thinkers, writers and artists were released from labor camps.

But for his old friends, who were completely cut off from Soviet Russia, Gorky’s return to Moscow was perceived as a real betrayal. The socialist Viktor Serge described him as a tragic figure, once a fierce critic of the Soviet regime, but somehow resigned to being silenced. But the truth was much more complex, and therein lay Gorky’s tragedy.

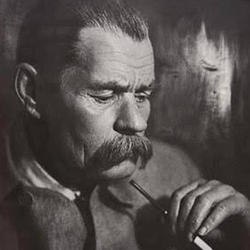

In 1932 he settled permanently in Russia, but over time his own ideas became increasingly at odds with Stalin’s practices. Still, he could not escape. Everywhere he went, people adored him. In Europe, however, sales of his books plummeted and he became completely financially dependent on the Soviet government. Moreover, he was banned from traveling abroad by Stalin.

But even in this invisible prison, Gorky continued to be a thorn in Stalin’s side. He opposed the Stalinist regime, subtly mocked it between the lines of his public writings, and in his essays on fascism he openly condemned totalitarianism in all its forms. In one of his notebooks, which was found and archived after his death, he even described Stalin as “a horrible flea that reached gigantic proportions with the propaganda and fear hypnosis it created on the people”.

There is evidence that Gorky was involved in a conspiracy against Stalin in 1934 with the right-wing leaders Rykov and Bukharin, the NKVD chief Yagoda and the Party’s Leningrad official Kirov. This explains why Stalin had Gorky’s son Maksim killed, because Maksim was helping to exchange information between his father and Kirov. In fact, this was probably the reason why Kirov was killed.

Gorky’s death remains a mystery. His health had deteriorated over the last few years. In addition to an old lung condition, he had a growing list of illnesses, including chronic flu and heart problems. Those who were with him in his last days are certain that he died a natural death. But in a show trial two years after his death, two of Gorky’s doctors were found guilty of medical murder for administering lethal doses of drugs to the writer on Yagoda’s orders as part of an anti-regime conspiracy allegedly led by Bukharin and Rykov.

Stalin may have used the writer’s natural death to eliminate his enemies. Gorky’s relationship with the opposition strengthens the possibility that Stalin may have ordered his death. We will probably never know the truth. What is certain, however, is that Gorky, whose ashes still rest in a niche in the Kremlin Wall, was sent off with full Soviet honor in a funeral procession led by Stalin himself, making him one of the cult icons of the Soviet regime.