n-tv.de / Von Hedviga Nyarsik

Dusty earth, charred tree trunks and the water fizzing out of the tap: large parts of western Europe are suffering from extreme heat and drought. All signs of what we will have to prepare for in the future.

The worst drought in decades is currently hitting households, factories, farmers and businesses in Western Europe. In many regions, the picture is the same: parched fields, dried-up riverbeds, empty wells. An exceptional summer? Not at all, say experts and warn: water shortages are becoming the new normal due to drier winters and scorching summers.

Climate researchers are more certain about future trends in temperature and heat than in any other area. When it comes to precipitation, there is much to be said for more extremes. But the models are uncertain on this point, especially for Central Europe, says Jakob Zscheischler of the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research. “With heat, it’s clear that it will continue as it has in recent years.” In all models, he says, it will get warmer, and in some it will even get extremely hot. “40 degrees in Germany is becoming the norm,” clarifies Peter Hoffmann of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “Today’s extreme years with 20 heat days will become average summers by the end of the century if we don’t take massive countermeasures in the coming years.”

- “Annie Live!” and “Arcane” Among the 2022 Emmys’ Juried Winners

- Abuse commissioner accuses EKD of sluggish investigation

- faz.net: One in four clinicians wants to quit

Calculations by the Federal Ministry of Transport’s network of experts illustrate the frightening forecasts: according to these, the 30-year average temperature in the summer months in Germany could be three to five degrees higher in the period 2071 to 2100 than in the comparable period 1971 to 2000. As a result, daily highs of over 45 degrees would then be reached at least as frequently as is currently already the case for the 40-degree mark.

According to these data, the number of hot days with 30 degrees or more could very likely range from 9.4 to 23.0 per year on average across Germany. By comparison, from 1971 to 2000, there was an average of only 4.6 such days nationwide. The number of summer days with maximum temperatures of 25 degrees and above could even rise to 39.5 to 63.8 (comparison period: 29.0). With tropical nights, when the thermometer shows no less than 20 degrees, 0.8 to 7.8 per year are possible. In the comparative period 1971 to 2000, the value was 0.1.

Fires destroy entire forests

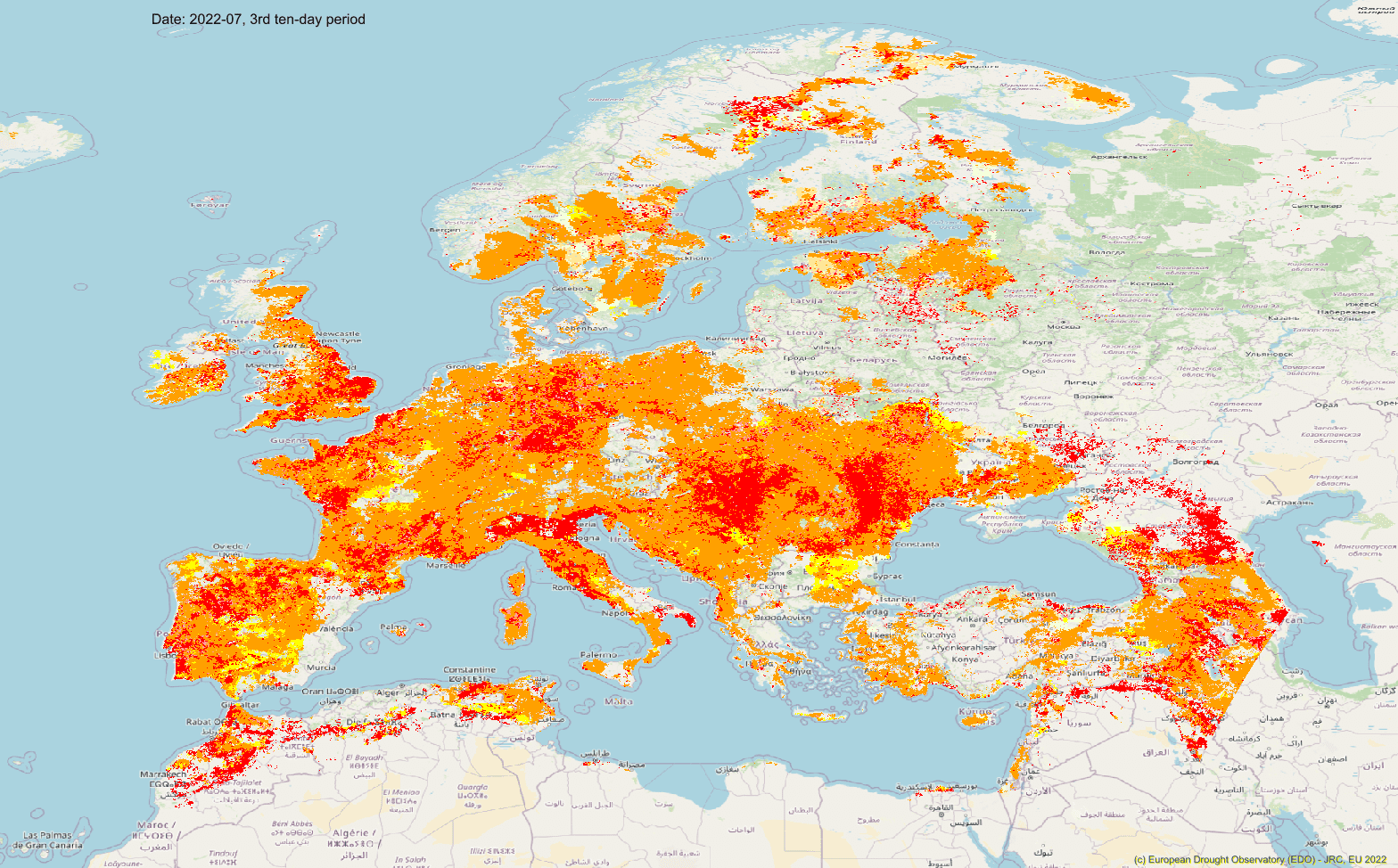

And it’s not just Germany that’s getting hotter. Climate researchers in other European countries are arriving at similar results in their models. The European Drought Observatory of the European Union (EDO) shows the effects of the extreme heat: In mid-July, a drought warning was in effect for nearly half of the entire EU area, with a red alert already declared for 15 percent. Since then, conditions have continued to worsen with new heat waves across the continent.

In Germany, for example, the water levels of Lake Constance and the Rhine recently reached lows. Inland skippers and farmers are particularly affected. Ships on the Rhine can only carry a third of their possible cargo. This is driving up prices for container, coal and grain shipments. The surrounding fields are also dry as dust. Farmers already fear for the corn harvest and late potato varieties.

In addition, forests are burning in many places. In Brandenburg, “the drought situation is the worst the state has ever experienced in its history,” says Interior Minister Michael Stübgen. The background, he says, is the lack of precipitation over the past five years and the severe drought this year as well. “We have already had over 400 fires as a result,” explains Stübgen.

In France, too, forests are on fire. Back in July, a fire near Bordeaux destroyed thousands of hectares of forest. Now the fires are flaring up again as a result of the extreme drought. Last week, Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne set up a crisis team to combat the drought, which is the worst since records began in 1958, according to Météo-France, the state weather service. The Loire River, which is more than 1,000 kilometers long, is so dry in places that it can be crossed on foot. Precipitation in July was 85 percent below normal, according to the weather service.

More than 100 French communities no longer have running water. Trucks cart in drinking water for local people, reports Christophe Béchu, Minister for Ecological Change and Territorial Cohesion. He looks to the future with trepidation: “We will have to get used to such episodes. Adaptation is no longer an option, but a duty.” Soil moisture is already at an all-time low, and the redeeming rain continues to be a long time coming.

Drinking water is becoming scarce

Spain is also struggling with extreme water shortages. The country is currently experiencing what is probably the driest summer in the last 60 years. According to the government, water reserves are at an all-time low of just under 40 percent. The heat is causing more water to be consumed, while natural reserves continue to fall – by 1.5 percent every week, according to reports from Madrid.

In the last three months, less than half of the expected precipitation for this time of year fell. 70 percent of the reservoirs in Spain can no longer meet the demand of their assigned region on a permanent basis. As a result, water use is being restricted in many parts of the country. Municipalities are turning off water at night, closing beach showers and banning pool filling.

This year is set to be the hottest and driest on record in Italy. “I don’t know what more we need to do to make the climate crisis a political issue,” said Luca Mercalli, president of the Italian Meteorological Society, most recently. “There is no comparable data in the last 230 years to the drought and heat we are experiencing this year.” These episodes would increase in frequency and intensity.

The drying up Po River illustrates the climate crisis with frightening clarity. The flow rate of Italy’s longest waterway has dropped to one-tenth of normal, and the water level is two meters below normal. In early July, the government declared a drought emergency in five northern regions and rationed drinking water there. Since then, trucks have been supplying the villages around Lake Maggiore.

Farmers fear for livestock and fields

The Netherlands also declared a water shortage last week. The government has not yet imposed restrictions on household consumption. But people are urged to think carefully about washing their cars or filling a pool.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Belgium, meteorologists reported the driest July since 1885. Despite a ban on farmers pumping out water for harvesting, groundwater levels are exceptionally low. Peatlands are in danger of drying up. And canals and rivers are also in poor condition: local authorities report that many fish are dying as only industrial or sewage water reaches them. Thirteen municipalities in the Ardennes have banned people from filling their swimming pools.

Meanwhile, in Switzerland, the dairy industry has been hit hardest by the drought: Authorities in Fribourg, Jura and Neuchâtel have had to open meadows in valleys not normally used for grazing until September, as pastures at higher altitudes have already dried up. In the canton of Obwalden, near Lucerne, the army had to use helicopters to transport water from a lake to the cows to keep them from dying of thirst.

“Every tenth of a degree counts”

Compared with other northern mid-latitude regions, such as the United States or East Asia, the number of heat waves over Europe has increased three to four times faster, according to a study published in early July in the journal Nature Communications. “With every additional tenth of a degree of global temperature increase, the probability of even hotter summers increases,” warns climate researcher Peter Hoffmann. There is an urgent need for action, he said. “Climate change is advancing and we know what possible future scenarios could look like. It is imperative that we act now to preserve the chance of stabilizing the global climate at well below two degrees.”

Physicist and climate scientist Friederike Otto of the Grantham of Imperial College London Institute also has powerful words on the current situation: “It’s hot in Europe and may get extremely hot,” she writes on Twitter. “These temperatures would have been lower if we had not burned fossil fuels. It also means fewer people would have died. Heat waves are by far the deadliest extremes in Europe.”

It’s not too late to act, experts say. “Even if we’re just getting started with climate protection today, we can still have an impact,” explains Andreas Becker, head of the DWD’s climate monitoring department. “Every tenth of a degree counts.”

the source used in the creation of the news: https://www.n-tv.de/