The discovery of the oldest DNA ever recovered reveals a stunning two-million-year-old environment in Greenland, including the presence of an unexpected explorer: the mastodon.

The DNA, discovered in sediments in Peary Land in Greenland’s extreme north, reveals what life was like at a considerably warmer epoch in Earth’s history. Trees, caribou, and mastodons formerly roamed the region, which is now a bleak arctic desert. Some of the flora and animals that formerly flourished there can now only be found in Arctic conditions, while others can only be found in more temperate boreal woods. “What we observe is an environment with no current equivalent,” says Eske Willerslev, senior author of the paper and evolutionary geneticist at the University of Cambridge.

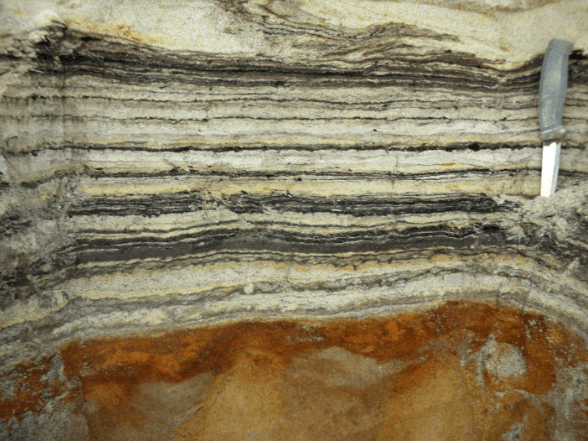

Until today, the oldest DNA found was in a million-year-old mammoth tooth. The oldest DNA ever discovered in the environment, rather than in a fossil specimen, was likewise a million years old and originated from Antarctic sea sediments. The newly discovered ancient DNA originates from a fossil-rich rock structure called Kap Kbenhavn in Peary Land, which retains deposits from both land and a shallow ocean-side estuary. The deposit, which geologists originally estimated to be roughly two million years old, has already provided a plethora of plant and insect fossils but no evidence of animals. The DNA research has revealed 102 new plant species, including 24 that have never been found petrified in the formation, as well as nine animals such as horseshoe crabs, hares, and geese.

“It’s painting a picture of everything that was present in this ecosystem, and that is really incredible,” says Drew Christ, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Vermont’s Gund Institute for Environment, who studies the history of Earth’s polar regions but was not involved in the research.

Using disembodied DNA fragments, the researchers recreated ancient Peary Land. DNA fragments can reach the environment every time a tree’s leaf falls, a person loses a little amount of skin, or a rabbit dies and decomposes in a meadow. The majority of these pieces, known as environmental DNA (eDNA), disintegrate fast. However, under certain chemical circumstances, DNA molecules can bond to sediments. According to Karina Sand, a molecular geobiologist at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute, this prevents them from being eaten away by enzymes.

The researchers began collecting sediments from Peary Land in 2006, but it took years for the technology to catch up with their ambitions. “Every time we had improvements in terms of DNA extraction and sequencing technology, we tried to revisit these samples—and we failed, and we failed,” Willerslev says. For years, the team was unable to extract usable DNA from the samples.

Finally, a few years ago, the researchers finally succeeded at extracting heavily damaged DNA. They were then able to compare the DNA fragments with the genomes of modern species. Similarities in sequences revealed that some of the species that left behind the DNA were among the ancestors of modern species.

Two million years ago the site of Kap København would have been a forested coastline where a river flowed into an estuary, Willerslev says. The river carried DNA fragments from land into the marine environment, where they were preserved. That’s why the researchers found evidence of horseshoe crabs—a family that lives much farther south today—alongside DNA from caribou. They also found evidence of coral, ants, fleas and lemmings.

The plant life dominating this landscape included willow and birch, which are found in southern parts of Greenland today. There were also trees now found only in more temperate forests, however, such as poplar and cedar, says study co-author Mikkel Pedersen, a physical geographer at the University of Copenhagen. Temperatures would have averaged between 11 and 19 degrees Celsius higher than today. But Greenland was at the same latitude as it is now—meaning this ancient landscape was bathed in 24/7 darkness for nearly half the year. The fact that plant life could survive despite long stints without sunlight is a testament to the power of evolutionary adaptation, Willerslev says.

The groups of organisms living in Greenland two million years ago were also able to survive and produce descendants, such as modern caribou, that now live in much colder Arctic conditions. Studying the genetic sequences of these ancient animals could reveal adaptations that could help Arctic species survive today’s human-caused climate change, Willerslev says.

Researchers aren’t sure how long environmental DNA can stay intact in sediments. Willerslev says he wouldn’t be surprised to find fragments up to four million years old. There could be other places on Earth where ancient DNA can help uncover how ecosystems changed as the climate oscillated, says Linda Armbrecht, a researcher now at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania in Australia, who led the study that discovered million-year-old DNA in Antarctic sediments and wasn’t involved in Willerslev and his colleagues’ new paper.*

“Both our studies have searched for DNA in cold environments: Greenland and Antarctica,” Armbrecht says. “Looking for DNA in environments and sediments with properties that are favorable for DNA preservation (including, for example, cold temperatures, specific mineralogy) seems to be key to unravel how far back in time this DNA can be preserved and detected.”

The main source of the news: https://www.scientificamerican.com