When we think of the Italian mafia, we usually think of men, fathers, who are the symbols of machismo, but we should not overlook the mothers. The first one of those mothers was Assunta Maresca, nicknamed Pupetta, who went down in the history books with the 29 bullets she fired in the street against the man who had murdered her husband, and who was famous for her beauty. This is the life story of Maresca, who recently passed away, which is like a novel or a movie…

The young woman sitting in the defendant’s chair shouted at the top of her lungs in the middle of the hearing, “I killed for love”.

She had caught the leader of the criminal organization who had killed her husband coming out of a coffeehouse on a hot August day and had taken her revenge. She had rained 29 bullets down on him (the police said that with that many bullets, they could have made several pencil batteries).

Her name was Assunta Maresca. She was born and raised in Castellammare di Stabia in Naples, in the south of Italy. From an early age, Maresca had a beauty that everyone looked up to, a beauty that had been recognized in competitions. Everyone around her called her “Pupetta”, a little doll.

Pasquale Simonetti, one of the rising young leaders of the Neapolitan mafia, could not remain indifferent to Maresca’s beauty. Pupetta was the perfect wife for a man like him who wanted to rise in the criminal world. Aside from her beauty, she was the daughter of a crime family notorious for her skill with switchblades. She was also very skilled with firearms; “There is no target I can’t hit between your eyebrows,” she boasted.

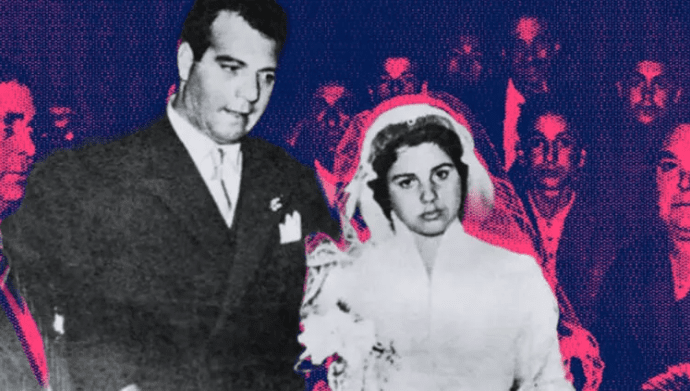

They married in 1955. Three months after their wedding, Simonetti was shot dead in Naples’ biggest square. It fell to 18-year-old Maresca, who was pregnant at the time, to avenge him.

Maresca was imprisoned for 10 years. When she came out, she was not just a young widow. She had already become a heroine in Naples’ criminal underworld. She had a reputation for sticking by her husband’s side no matter what, for not backing down, and had gained a wide following.

She had become the lady squire of the Sicilian-based Camorra organization that controlled the Naples region; they called her “Lady Camorra”. During her trials, as she traveled back and forth between the prison and the courtroom, other members of the Camorra (i.e. the Camorristi) would throw flowers on the roads she passed. He was like royalty greeting the public in a horse-drawn carriage.

You might be saying, “I remember that name from somewhere”. You would not be wrong, because when Maresca passed away on December 29, 2021, he made headlines around the world.

A book that recently hit the shelves brought this interesting woman to the agenda once again. Written by journalist Barbie Latza Nadeau, “The Godmother: Murder, Vengeance, and the Bloody Struggle of Mafia Women” by journalist Barbie Latza Nadeau shed light on the lives of Maresca and other female mafia leaders in ways we have never seen before.

Nadeau’s interviews with Maresca in the summer of 2019 and the young woman’s rise to legend were recently published in The Daily Beast. Here is the incredibly detailed life story of the “doll” who wrote her name in the history books with a murder 67 years ago…

* * * * *

Maresca tapped her manicured nails, painted with black nail polish, on the white marble table. Looking at her small hands, her skin that looked too soft for a woman in her 80s, the age spots on her hand, it was hard to believe that these fingers had once pulled the trigger of a silver .38 Smith & Wesson.

Maresca rained bullets down on her husband’s adversary. The man had undoubtedly died soon after being hit in several places, but Maresca had kept firing at the lifeless body lying in a pool of blood. (When her own gun was empty, she had grabbed her 13-year-old brother Ciro’s pistol and continued.)

He said he still kept the gun in his bedside drawer. But he would not show it to anyone who asked to see it. “I only take my gun out when I’m going to use it,” he jokingly told Nadeau. She was a funny woman for those who could get beyond the fact that she was a cold-blooded killer.

HE STABBED A GIRL IN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

His father was not at the top of the mafia hierarchy, but he was an important gang boss. Castellammare di Stabia and several small neighboring towns were under his control. He was well known and respected in the criminal world. His specialty was cigarette smuggling. He made a lot of money this way in the post-war period.

The Maresca family men were known as Lampetielli, the lightning bolts. They were so named because of their skill with switchblades.

This was Maresca’s first brush with the law. When he was still in elementary school, he stabbed the daughter of another local crime syndicate member. The stabbed girl, however, suddenly stopped testifying and the charges were dropped. Years later, Maresca would characterize the incident as an exaggerated childhood quarrel. But that didn’t change the fact that he knew how to use a gun before he was a teenager.

“THE PRESIDENT OF PRICES” OR THE GREAT PASQUALE

Although her four brothers did their best to protect Maresca from the unpleasant attentions of the men around them, they were not always successful. From a very young age, she realized that she could use her beauty to get anything she wanted, and she never failed to take advantage of it.

This was how she had gotten Pasquale Simonetti, one of the young bosses of the Camorra. Simonetti, whom everyone around him called Pasqualone ‘e Nola (Big Pasquale of Nola), lived up to his name. He was a mountain of a man, with jet black hair, a round chin and a thick neck. He was over six feet tall. Pupetta was really as small as a doll next to him.

He was a classic Camorra leader. He was wealthy, well-dressed and ruthless. He had a reputation in the underworld for extortion, coercion and murder. Before Maresca entered his life, he was known as “the president of prices”. He ran the Camorra’s racketeering operation, extorting fruit and vegetable growers and vendors. The tomatoes, pumpkins, potatoes, peaches and lemons produced in the fertile fields of Naples were a lucrative industry, generating annual profits of $250,000 ($2.2 million in today’s money).

In 1952, Simonetti was sentenced to 8 years in prison for the attempted murder of Alfredo Maisto. Maisto, who had worked with Simonetti in the past, eventually declared his independence and became a rival.

When Simonetti went to prison, one of his men, Antonio Esposito, took over the management of vegetable prices. Esposito promised to pay Simonetti his share while he was in prison. He kept this promise for the first few months, but soon his greed for money took over.

Simonetti was released in the second year of his 8-year sentence. New evidence was said to have emerged, but it was also possible that the judge had been threatened or bribed. Naturally, he wanted to go back to his old job and resume his fruit and vegetable extortion, but Esposito was not about to give up the money he had been making for two years so easily. Simonetti, however, was too preoccupied with other things to notice the rising tensions.

THEIR LOVE STARTED WITH LETTERS IN PRISON

In the two years he spent in prison, he realized a very important truth: He did not want to live alone. He had observed how the visits of other inmates’ wives and lovers enriched their lives and he wanted to do the same. He had gotten to know Maresca through a beauty contest she had won shortly before her imprisonment and was determined to marry her.

After his imprisonment, they began exchanging letters. He responded enthusiastically to Maresca’s letters, writing that they would spend their lives together. Within days of his release, he openly sued Maresca. His brothers, who had said no to other suitors, gave the green light to the marriage, believing that Simonetti’s rise would benefit them as well.

On April 27, 1955, when Maresca was only 17 years old, they married in a Catholic ceremony attended by more than 500 guests. At the wedding, attended by the leading figures of the Camorra organization, the bride and groom were presented with gifts worth a small fortune. Even Simonetti’s rivals, such as Esposito and Gaetano Orlando, went to the church to celebrate the wedding that tied two important crime families together. Everything was perfect. Life was not going to be easy, but at least it looked like they would spend many years together.

As Maresca tells it, they were determined to get away from crime and do something less risky. But in reality it was almost impossible for them to do so. Not only did they lack the skills to get a decent job, but there were not many people who would have the courage to employ people so closely connected to crime. In fact, it was rare for such criminal families to leave their children alive if they wanted to make their own way.

KILLED WHILE PEELING ORANGES

In mid-July, three months after the wedding, Simonetti died of gunshot wounds in the middle of the square where the city market was held in Naples. He had gone to the market to collect tribute and pay his share to the farmers under his protection. He was shot while peeling an orange offered to him by one of the vendors. It was later claimed that the orange had been given to him as a distraction and that the assailant had not acted alone. The square was packed, but no one saw who pulled the trigger. Except Simonetti.

Simonetti, who was rushed to the hospital, had been dying for 12 hours. Maresca stayed by his wife’s bedside until her last breath, praying with tears in her eyes. In a brief moment of lucidity, Simonetti whispered the name of his killer to his wife. He said it was Gaetano Orlando, a hit man who had been at their wedding. It was Esposito, who wanted to be head of the fruit and vegetable rackets again, who had instigated Orlando, Simonetti said.

Maresca, who buried Simonetti, whom he called “My Prince Charming” for the rest of his life, a few days later, vowed revenge even before he left the cemetery. In those years, it was unheard of for a woman to make such a claim.

Maresca told Nadeau, “Those days were very long and lonely. It was either melt away or make things right. I decided I had no choice but to make things right.”

She also said that the main reason was that the police did nothing. Despite being an 18-year-old pregnant mafia widow and daughter, she believed in the rule of law and told the police verbatim what her husband had told her. At some point Orlando was caught and sent to prison, but the prosecution was reluctant to investigate Esposito’s role, saying, “We need evidence.” According to Maresca, either they didn’t dare mess with Esposito or they were outright protecting him.

Esposito was sure that Simonetti’s death would be avenged. That’s why he started threatening Maresca, confusing him with various games. “If you do anything, you and your baby will disappear, they won’t even be able to trace you,” he sent her messages. But she had made the grave mistake of underestimating Maresca.

AVENGED HER HUSBAND AT THE PLACE WHERE HE WAS KILLED

On the day she buried her husband, Maresca decided not to let Esposito get away with the murder. When she left the house that day, she put Simonetti’s gun in her purse and never took it out again. As the children of a gang leader, both he and his brothers knew how to use a gun very well. Their father had taught them personally…

It was about three months after Simonetti’s funeral. Maresca’s pregnancy was well advanced. Maresca took her 13-year-old brother with her and went to the cemetery to visit her husband’s grave. They were also going to stop by the market where Simonetti had been killed to buy fruit and vegetables.

On the way to the market, Maresca noticed Esposito coming out of one of the coffee shops on Corso Novara. They were very close to the spot where her husband had been shot. As Esposito walked along Corso Novara, Maresca asked her driver, Nicola Vistocco, to drive towards him. When they were close enough, she stopped the car, got out and started shooting at him. A gunfight ensued, but Maresca jumped in the car and quickly left the scene. Although the driver testified that he saw nothing, both he and Ciro were charged with aiding and abetting murder and sent to prison.

Maresca initially said he was trying to open the door of Esposito’s car and opened fire in self-defense. He said he did not remember firing 29 shots and that he pulled the trigger “once or twice” from where he was sitting in the back seat. But the evidence, especially the autopsy photos, said otherwise. He had deftly used Simonetti’s Smith & Wesson, then grabbed his brother’s revolver to make sure Esposito was dead. Five of the bullets had hit the man in the head.

EVERY WORD BECAME AN EVENT DURING THE TRIAL

After a few weeks in hiding, Maresca went to the police, confessed to what she had done and was arrested. Despite everything she had done, she found it strange that she was immediately put on trial while the instigator of her husband’s murder was not. She thought this meant that Esposito controlled the local police or was an informer.

During the trial, she showed not the slightest sign of remorse, even saying, “I would do it again if I had the chance.” From day one, she said that it was her duty to avenge her husband’s death in lawlessness. “I killed for love,” she said and fainted. The local newspapers followed the hearings day by day, every word she said in court made the headlines. The reports, which included details such as what she wore and how she batted her long eyelashes, treated Maresca like a star.

The prosecution characterized Maresca’s revenge for her husband’s death as part of a gang war and demanded life in prison. At first her lawyer argued self-defense, repeating the argument Maresca had made in her first testimony. However, when the woman’s cry of “I killed for love” negated this defense, her lawyer resorted to the “diletto per amore” defense.

This title, which we can translate into Turkish as honor or honor murder, was used in Italy in those years to describe crimes in which heartbreak was used as an excuse. In those years, such murders were so common that it was considered a mitigating circumstance until the mid-1990s to say “I protected my honor” or “I defended my honor”. Although less common, such defenses can still be used today, especially in cases such as femicide.

NO ONE DARED TO BREAK THE VOW OF SILENCE

Gaetano Orlando, who fired the gun that killed Simonetti, was tried simultaneously with Maresca. Both trials were conducted in public. Esposito’s men never left the courtroom empty for a single day, making sure that the “omerta”, the code of silence adopted by all organizations in the Italian mafia, was enforced. Almost none of the 85 eyewitnesses called to the stand said anything. No one had seen anything, no one knew anything. And the few who did speak were not likely to influence the court’s decision.

Avenging her husband’s death had an unexpected consequence for Maresca. She became an icon in the underworld of Naples, earning the title of Lady Camorra, the first of the “madrina” or mafia mothers.

RELEASED EARLY IN THE FACE OF THE INFORMATION HE PROVIDED

Maresca’s trial was short-lived. The young woman was sentenced to 24 years in prison. On appeal, her sentence was reduced to 13 years and 4 months, and she was released before 10 years were up. In 1965 she was granted a special amnesty. Her lawyers had negotiated a deal to reduce her prison term in exchange for information. However, Maresca denied this to Nadeau, saying that new evidence had emerged that Esposito had killed her husband and that the judge had finally seen the truth.

Nadeau recounted this conversation in his book: “Although the assistant to the prosecutor who made the deal confirmed that Pupetta’s information was the reason for the reduced sentence, there was no point in confronting her with the truth. After all, this woman had repeatedly shown that she had little respect for what Italians call verita (truth).”

The book by Barbie Latza Nadeau, a US journalist who has been living in Rome for nearly 25 years, also mentions mothers other than “Pupetta”. Maria Angela Di Trapani, who “reorganized the entire Sicilian Cosa Nostra”; Cristina Pinto, nicknamed “Nikita”, who ordered the deaths of many people, including an 11-year-old boy; Maria Licciardi, who killed 14 of her enemies in 48 hours in the late 80s; Maria Campagna, the Cosa Nostra boss who “cleansed” 150 people with her husband; and Anna Addolorata De Matteis Cataldo, known as “Anna Death”. Cataldo had a woman murdered, her body burned and then dumped in a cistern. Not wanting to leave a trace, he also ordered the murder of the woman’s 2-year-old daughter.