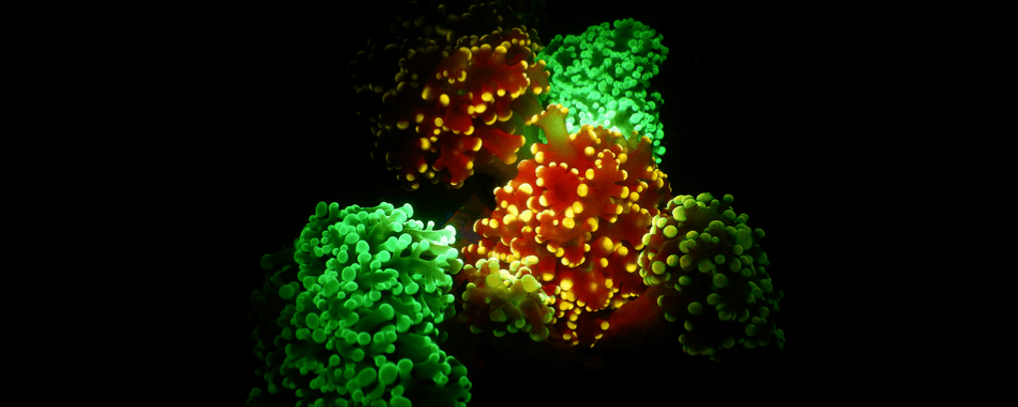

The oceans are home to a variety of wonderful marine life that has given rise to diverse ecosystems. Corals, which come in a wide variety of forms, dimensions, and hues, are no exception. Even some animals light at night.

A group of Israeli scientists has now determined why that might be the case. Deep-reef corals may emit dazzling colors from their luminous green and yellow tentacles to entice creatures to feed on them.

Or Ben-Zvi, a coral reef expert at Tel Aviv University, led the study. “Despite the limitations in the current understanding regarding the visual interpretation of fluorescence signals by plankton, the new study gives experimental evidence for the prey-luring role of fluorescence in corals,” he says.

Most reef-building corals take advantage of the sunlight that filters down from the ocean surface by basking in the shallow waters where their resident algae can absorb it. These are the coral reefs that we are familiar with and adore, complete with photosynthetic zooxanthellae.

Other hardy coral species, however, are able to develop up to 6,000 meters (20,000 feet) beneath the surface in the cold, dark depths of the ocean. (Unfortunately, they cannot avoid the effects of people.)

The authors of this new study hypothesized that, like other deep-sea inhabitants that produce bioluminescence, these fluorescent deep-water corals would employ light to entice their food, like tiny plankton, into their fold.

But they had to put that notion, which they called the “light-trap,” to the test.

Yossi Loya, senior author and marine ecologist at Tel Aviv University, explains that many corals exhibit a bright color pattern that draws attention to their mouths or tentacle tips.

For corals that are rooted to the bottom, being able to glow and draw in prey appears to be a rather crucial adaptation, “particularly in settings where corals require additional energy sources in addition to or as a substitute for photosynthesis,” says Loya.

However, a number of additional theories have been put out to explain why coral fluoresces. For instance, the “sunscreen” idea postulates that fluorescence may shield corals that have bleached from additional heat stress and light deterioration. Another explanation would be to increase photosynthesis.

There is currently no proof that the fluorescence of mesophotic corals, which thrive in low, blue-shifted light, provides any form of defense or energy boost.

Therefore, Ben-Zvi and her coworkers went in and began studying coral species that develop at light-diminishing depths and rely more on predation than photosynthesis for nutrition.

The scientists evaluated whether teeny shrimp (Artemia salina) preferred a green or orange fluorescent target over transparent, reflecting or matt-colored targets placed on the other side of a tank in a series of laboratory studies.

In fact, the shrimp were drawn to the fluorescent signal and swam that way.

When the scientists conducted trials at the Gulf of Eilat, which is situated near the northern edge of the Red Sea, they came up with similar outcomes. Anisomysis Marisrubri, a natural crustacean that is eaten by corals in the Gulf, preferred fluorescent cues to reflective targets, but not an invasive species of fish larvae.

Finally, the researchers evaluated predation rates among various colored Euphyllia paradivisa corals that were brought back to the lab after being taken from the Gulf of Eilat at depths of 45 meters (148 feet).

In contrast to their yellow-fluorescing counterparts, fluorescent green corals actually enjoyed better predation rates, devouring more A. salina shrimp in a 30-minute period. Additionally, there was no difference in the amount of shrimp consumed when the experiment was performed using red lights instead of blue ones, which do not activate coral fluorescence.

The yellow morph of E. paradivisa was discovered to be the least abundant in its natural environment in the mesophotic reefs of Eilat, which can now possibly be explained by the decreased prey attraction to this color revealed in the present study, according to Ben-Zvi and colleagues.

It’s vital to remember that only one type of mesophotic coral was examined in this study. The perception of color by plankton and other crustaceans that support coral reefs also need further study because it probably varies depending on the species, the environment, and the stage of life.

In any case, the study’s findings highlight the need of protecting corals, which form the foundation of the biodiverse ocean ecosystems. Fortunately, we know how.

Published in Communications Biology was the study.