![]() This July 1 marked 25 years since the United Kingdom returned Hong Kong to China.

This July 1 marked 25 years since the United Kingdom returned Hong Kong to China.

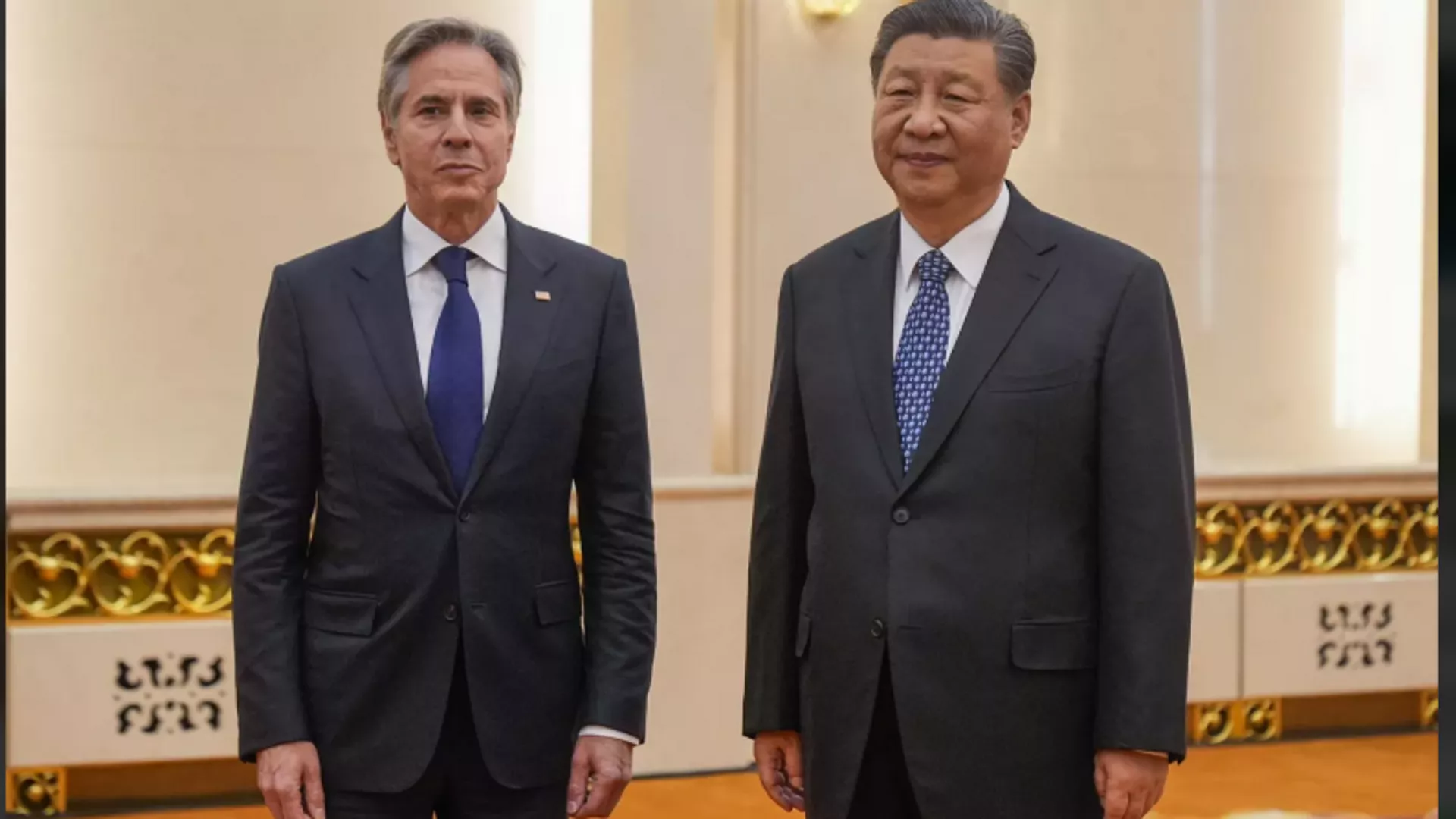

And on this anniversary, Chinese President Xi Jinping insists that Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” model has worked to protect the city and should remain in place for the long term.

The Chinese leader defended this political system in Hong Kong, despite recent international criticism for enacting certain laws in the territory that undermine freedom of expression and dissent.

However, despite celebrating a quarter of a century since it was returned by the United Kingdom, Hong Kong is not all about celebrations.

- U.S. Supreme Court limits Biden’s powers to fight climate change in landmark ruling

- Attention WhatsApp and Telegram Users!

A large part of the inhabitants of this Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China have grown up under a political and economic system very different from that known to their compatriots on the mainland.

That is why many feel Hong Kongers do not have the best impression of China.

As usual, the anniversary of the handover revives concerns about the future of the concessions negotiated with the British to secure the return of the territory they forcibly seized more than 150 years ago.

Under “one country, two systems,” Hong Kong is supposed to be governed in a way that gives it a high degree of autonomy and other rights not found in mainland China.

But this is a status that more and more critics are calling into question, especially since the 2020 imposition of the National Security Law, which for many has spelled “the end of Hong Kong.”

Spoils of war

Indeed, the British annexation of Hong Kong Island occurred at the end of the First Opium War in 1842, and is one of the earliest examples of what later became known as “Gunboat Diplomacy”.

By that time, the UK was importing almost all of its tea from China, but was unable to get the people of China interested in any of the British exports.

Until the British East India Company found a product with which to balance the unequal balance of trade: opium.

The drug was quickly banned by the Chinese authorities, so the British turned to smugglers.

And when Emperor Daoguang complained that this illegal trade was causing millions of addicts, his protests were simply ignored.

In 1839, however, Chinese authorities confiscated some 20,000 chests of opium.

And London responded by sending a small army that within a few years completely defeated the Chinese forces and forced Peking to sign a humiliating peace.

Among the conditions imposed by the Treaty of Nanking were the payment of 21 million silver dollars in reparations and the opening of several of the country’s ports to all merchant ships.

And, above all, the cession in perpetuity of Hong Kong Island, to which the British would later add the neighboring Kowloon Peninsula in 1860.

This new concession was also wrested by force at the end of the Second Opium War, when the United Kingdom also forced China to allow the drug trade.

And the current territory of Hong Kong was formed in 1898, when China agreed to a free lease of the so-called New Territories – and 235 surrounding islands – for a period of 99 years, expiring in 1997.

“One country, two systems”

According to historian Diana Preston, the British delegate who negotiated the last cession, Claude McDonald, chose a 99-year term because he thought it was “about the same as forever.”

But the growing importance of the New Territories – which make up 86% of Hong Kong’s territory and are home to more than half the population – eventually made the division of the colony impractical.

And with an increasingly powerful China determined to reverse treaties it considered unfair, talks on a possible renewal of the lease eventually turned into negotiations on the return of all of Hong Kong.

By 1982, when negotiations began, the territory had nevertheless become one of the world’s leading financial and commercial centers.

Nor could its political system be any more different than the communist model of the People’s Republic of China, where a single-party system has been in place since 1949.

In recognition of these differences, China agreed to govern Hong Kong under the principle of “one country, two systems”, pledging that the territory would enjoy a “high level of autonomy, except in defense and foreign affairs” for the next 50 years.

Thus, in practice, this Special Administrative Region has its own legal system, multiple political parties and rights including freedom of speech and assembly.

And the mini-constitution enshrining these rights, known as the Basic Law, clearly states that “the ultimate goal” is for the territory’s leader to be elected “by universal suffrage” and “in accordance with democratic procedures.”

However, China has been criticized in recent years for increasing its control over Hong Kong and enacting laws and reforms that stifle free speech and dissent.

A democracy issue

The right to directly elect the chief executive – the position that with devolution came to replace the governor who was previously appointed by London – has been the subject of a years-long struggle in the old colony.

The latter is elected by a committee of 1,500 members, mostly considered sympathetic to Beijing.

In 2021, in a sign of China’s growing influence, Beijing passed a resolution that fundamentally changed Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (LegCo).

Under the new “patriots” law, all LegCo candidates must be vetted by a separate selection committee, making it easier to veto anyone deemed critical of Beijing.

It also drastically reduced the proportion of lawmakers who can be directly elected by the people, from 50% to 22%.

As of 2022, almost all LegCo members are Beijing sympathizers.

The city’s chief executive election also saw John Lee, a staunch Beijing supporter and the only candidate in the race, appointed to the post.

When in 2014 the Chinese government said it would allow direct election of the chief executive, but only from a list of candidates duly pre-approved by Beijing, Hong Kong experienced massive protests.

Many in the territory have watched with concern as China increasingly intervenes in other aspects of Hong Kong politics, generally against its more liberal tradition.

But there are also those who want the Communist Party of China to have greater influence in the affairs of the Special Administrative Region.

In 2020, China introduced the controversial National Security Law for Hong Kong, which in practice facilitated the persecution of dissidents and protesters and reduced the city’s autonomy. So much so, that many critics called it “the end of Hong Kong.”

Hundreds of protesters, activists and former opposition lawmakers have been arrested since the law went into effect.

The divisions between pro-Beijing citizens and those calling for more autonomy are particularly evident during the anniversary of devolution, especially as 2047 approaches.

After that date, China will no longer be obliged to maintain the autonomy agreed with the UK for the handover.

Some believe Hong Kong should seek independence, but China is unwilling to consider that option.

Which means that the possibilities range from an extension of special status to complete loss of autonomy.