The ancient Greeks developed contradictory ideologies for “masculinity”, from Spartan muscle flexing to Athenian cunning.

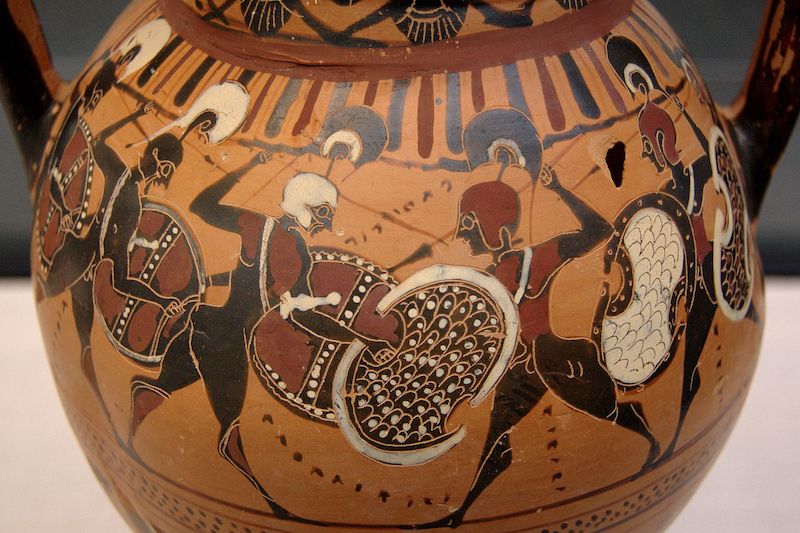

For the ancient Greeks, being masculine meant being brave. So there was a word called andreia, which meant both masculinity and courage. There were many ways to prove one’s courage, and perhaps the most critical was on the battlefield. When it came to weapons, no one seemed more qualified than the Spartans.

For the Spartans, courage was the number one virtue and the highest honor was to die fighting on the battlefield. Loyalty, self-control, endurance, refusal to fear and obedience to orders were exemplary traits. So much so that those unfortunates who behaved cowardly on the battlefield, the “tremblers”, were forced into exile or suicide.

- The Rally that Paved the Way for Women’s Participation in Modern Life: Women’s Sunday

- Thousands of years old shoes emerged from melting ice in Norway

Prof. Paul Cartledge of Cambridge University, an authority on ancient Greece, says: “In ancient Greece, one was not born a man; masculinity was a status that could be acquired, maintained or lost. In Sparta, where war had more cultural meaning than in Athens, masculinity was proved in battle.”

Of course, masculinity was not just about shedding blood or showing courage in the face of danger. Greek warfare was seasonal (there was a time for everything in Greece) and most city-states did not raise a full-time professional army like the Spartans. Instead, for most Greeks, being a kyrios, or master of the house, meant providing a daily dose of masculinity.

Radish punishment

Greek men were proud men and violating the rules of the oikos or household was seen as an attack on the kyrios’ manhood. The harshest punishments were reserved for intruders in the bed. If caught red-handed, the cuckolded husband was allowed to kill the trespasser. But if the situation was discovered later, the punishment was limited to heavy fines, meaning that once the passion had been quenched, there was time to discuss compensation.

For those who were tight-fisted, there were alternatives: to say goodbye to their genitals or to be sodomized with a large radish (apparently this was actually happening). It may seem trivial, but revenge played an important role in the Greek mentality and was closely linked to notions of masculinity, survival and prosperity. So a “real man” would know how to defend himself and his family/property, even with a vegetable.

Of course, there were wise men like Socrates who argued that doing wrong was worse than suffering, but let’s face it, they were a minority in a world where the Achilles version of masculinity prevailed.

Strong women in Sparta?

Because of what they were taught from birth, family life was seemingly secondary for Spartans. Loyalty to the state came first. For them, the army was their home and their comrades in arms were the real family.

Marriage was nevertheless important because of the training of future citizen-soldiers. For this reason, men who delayed marriage were publicly shamed, while those who had more than one healthy son were praised. Since men were mostly preoccupied with the world of war, women acted as masters of the home. In de facto terms, they had much more freedom and power than women in Greece, who were legally relegated to the status of minors and under the control of their husbands (although it can be assumed that some couples lived more equally). Spartan women managed the day-to-day money, ran the businesses and were responsible for the slaves who took care of the household.

The old-fashioned Aristotle was not impressed by the Spartan situation. He believed that nature intended men to dominate women. In Sparta, however, their peculiar definition of masculinity seemed to have the opposite result.

But this was only in appearance. Prof. Cartledge notes, “Unlike Athenian women, adult Spartan women could both own and dispose of landed property. Spartan men, unlike Athenian men, did not feel that their masculinity was diminished. Despite the apparent ‘freedoms’ that Spartan adult women, unlike Athenian women, enjoyed, everything was still masculine. Because their warrior values governed the form of government and society as a whole. Men held the upper hand, including controlling the sex lives of their wives.”

“Be a man”

As paternity, which in Athens was related to the family lineage, was often reduced to a patriotic duty in Sparta, paternal rights and responsibilities diminished. Infanticide was common in these regions, but the Spartans may have taken matters to a new level by applying the principle of “survival of the fittest”.

When an Athenian couple left an unwanted baby, they would take certain steps to ensure that the baby survived and was raised by another family. But in Sparta, unwanted babies were known to be released into nature and wild animals, guaranteeing death. All babies were brought before the “old men of the tribe” who supposedly examined them for physical defects. If deemed unfit, the child was left to die, regardless of the wishes of the family.

However, a recent study suggests that the situation may have been more complex. Archaeological evidence suggests that some disabled babies were indeed fed.

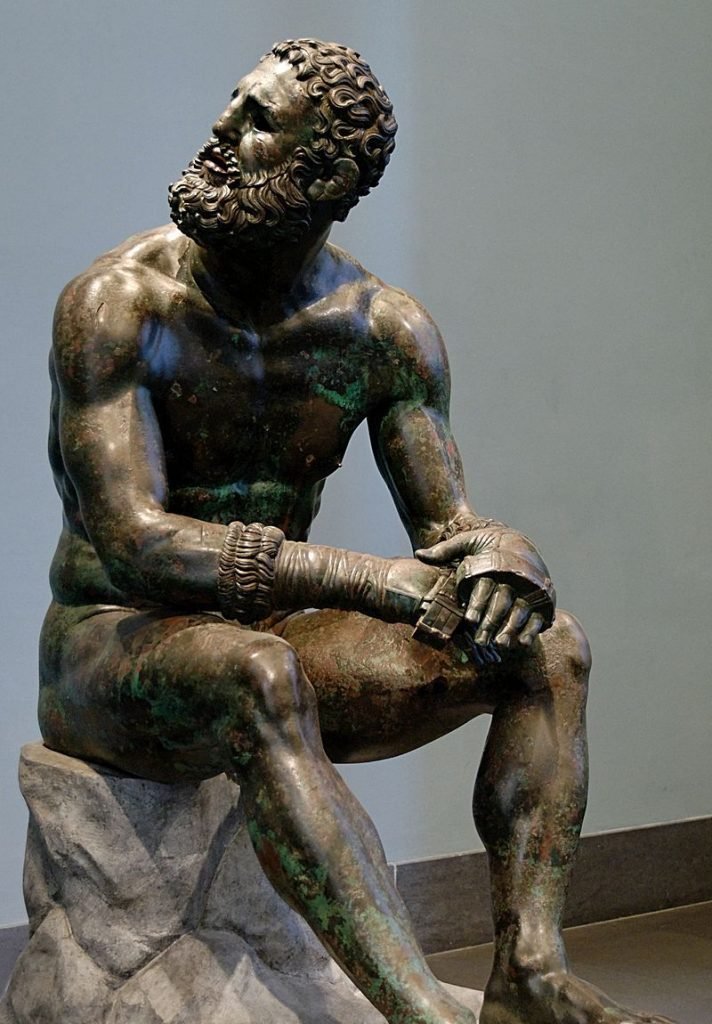

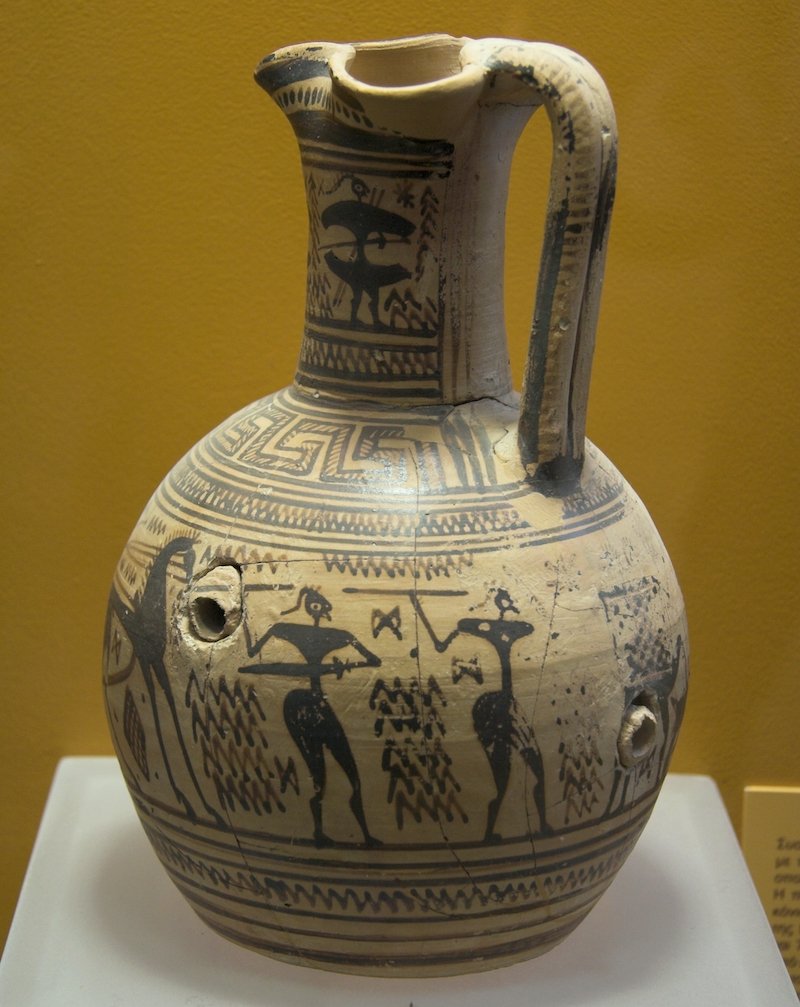

Fit Spartan boys faced tests linked to the broader concept of masculinity “Andragathia”, which implied bravery in battle, but also included demonstrating other virtues as a citizen, such as comrade solidarity.

“In Sparta,” Cartledge writes, “this kind of masculine virtue was achieved by successfully passing a compulsory examination between the ages of 7 and 18, which was unique in all of Greece. This was the educational system known as Agoge, or ‘Cultivation’.”

The training program was designed to turn young blood into professional warrior-citizens. Young soldiers in communal barracks were introduced to the world of men: combat, endurance, survival, hunting and athletics. They were also objects of desire and forced into pedophile relationships under the guise of training.

Cartledge suggests that paedophile relationships were not necessarily widespread, let alone institutionalized norms in roughly all 1,000 ancient Greek cities. “I think Athens and Sparta were exceptions for different reasons. Sparta in terms of education. Athens socioculturally.”

Thebes developed another approach that encouraged adult male/male homosexuality in the army. This, they believed, deepened the bonds between soldiers and enabled them to fight more effectively, especially when a lover fell during battle. The Theban special force known as the Sacred Band of Thebes would tell you no different.

This elite unit was formed in the 4th century BC under the leadership of the observer Gorgidas and consisted of 150 same-sex couples. Operating at the forefront of the offensive, the “Gay 300” were responsible for ending the long-standing Spartan domination of their territory.

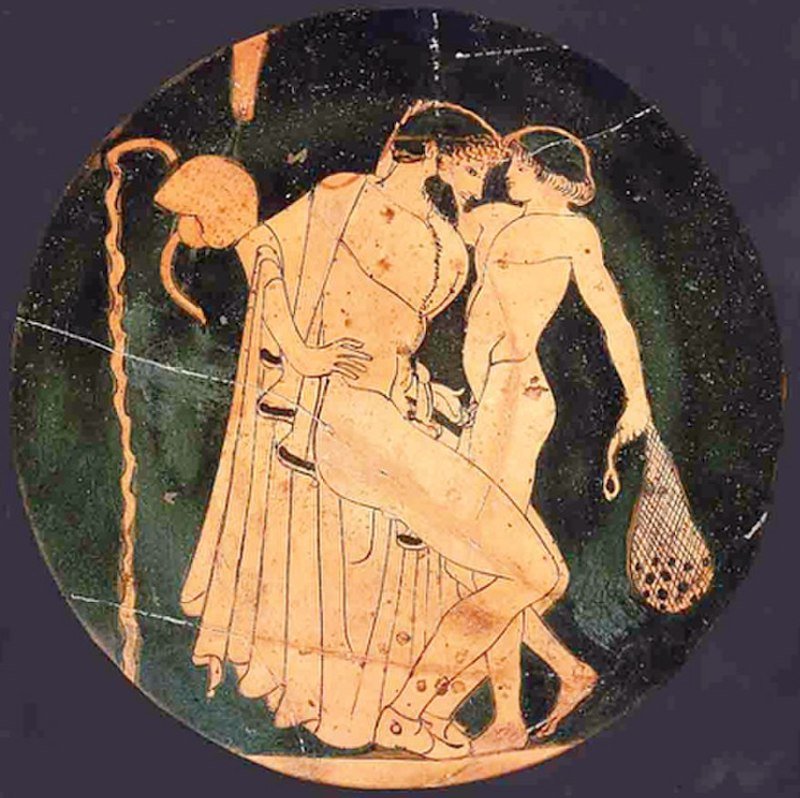

Active vs. Passive

One thing is certain, ancient Greek men were quite free in their sexuality. There was no shame in seeking the services of sex workers, as a bit of sex work was a key aspect of masculinity. There was nothing wrong with engaging in extramarital affairs. There was no shame in being turned on by another man (male beauty was sacred), especially if he was a pretty boy (depending on the era and the city).

After all, for many Greeks, male sexuality was more about power dynamics than age or gender. In bed, it was all about two things: active and passive. Being passive, i.e. playing the “female role” by penetrating, was the most unmanly thing a man could do, while being the “penetrator” was an act of dominance and power. A “real man” could only play an active role.

Because of this reasoning, free citizen men often did not openly engage in adult homosexual relationships for fear of being labeled “effeminate” because one was clearly on the “passive” side.

“Athenian men who willingly submitted to anal penetration in adult life were mocked as kinaidoi, a term of abuse with connotations of femininity,” Cartledge explains. Sparta was therefore quite ‘normal’ (for once) in not using adult male/male sexual relations in military service.”

It was quite easy to destroy a man’s reputation. All one had to do was accuse him of sexual perversion. One such attempt at defamation was the accusation of Marcus Antony of teenage prostitution and passive homosexual acts for political gain during the Roman Republic.

Words can kill

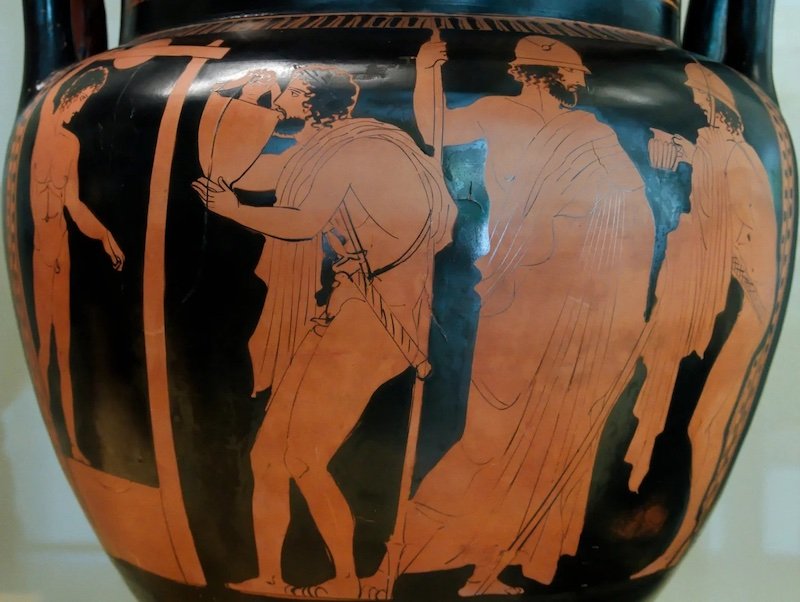

Enough about male-male love. Let’s get to the heart of the matter. In Athens, the ultimate battleground for men was the political arena. Therefore, the most powerful men, the “manliest” men, were politicians. Their sharpest weapon was rhetoric, unlike the Spartans, who were proudly laconic.

“The Spartans did not favor the elaborate rhetoric of, say, an Athenian politician like Demosthenes, but they could be eloquent in their own way when they wanted to be. For the Spartans, being laconic was not parsed as an essential feature of being male, and so they did not think that the ornate rhetoric of the Athenians was in itself feminine.”

Perhaps an Athenian’s favorite pastime was to destroy a rival in a public debate, a pastime that was probably foreign to the Spartans. A skilled orator could quickly deprive his opponent of his “social penis” (masculinity was hard to gain and easy to lose).

The consequences of public shaming could be severe. Exile and ostracization were offered as a courtesy for those who “needed” to be apart for a while.

For Aristotle, all men were political animals (happiness requires companionship) who could not flourish on their own outside the city and its agora.

For most Athenians, the choice was simple: they could either accept being called a “fool” (someone who kept to himself) or they could embrace the ups and downs of a full-fledged citizen. A respected member of Athens was not only the master of the house, but also had to be actively involved in the political life of the city. All male citizens over the age of eighteen were expected to attend the monthly meetings of the assembly (ekklsia) and vote on all matters, great and small. Freedom of speech, a privilege unknown to Athenian women, was at the heart of the assembly and therefore all men, regardless of one’s status, could, at least in theory, express their opinions, dissatisfaction, concerns and support. In Athens, simply being politically active could be the ultimate testosterone booster.

Haaretz. May 9, 2022. utilized