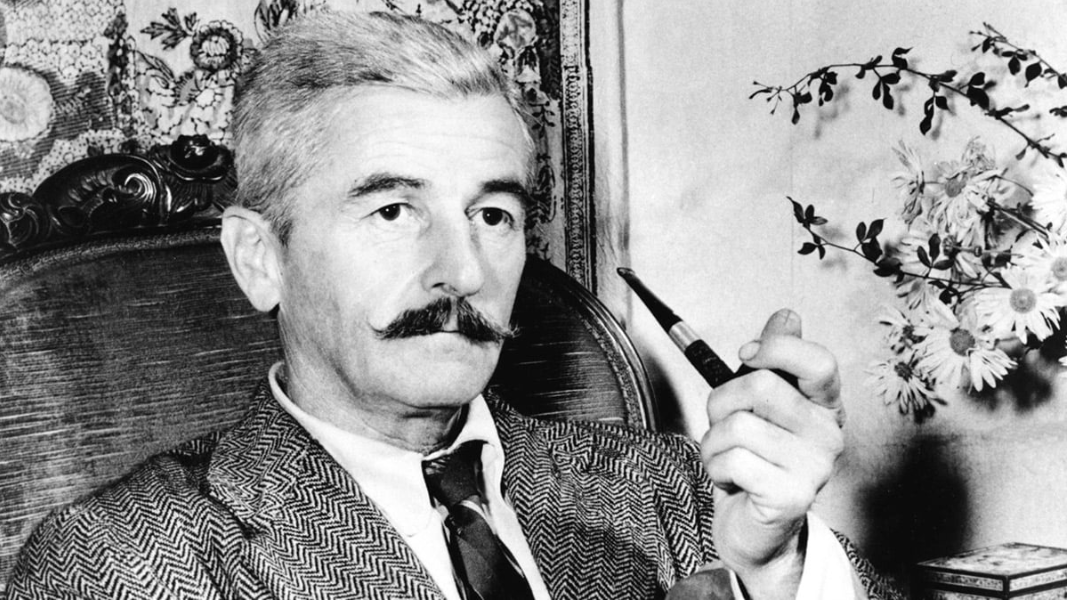

In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature in Stockholm on December 10, 1950, William Faulkner said that the only thing that makes good writing possible is ‘the human heart at odds with itself’. Faulkner had such a heart. He was a man of contradictions and inner conflicts in his own life. In his letter to Malcolm Cowley dated February 11, 1949, he wrote that he was a ‘special individual’. He really was, thanks to his inner contradictions.

What makes William Faulkner so different and so special in Southern literature is that he is, in Tim A. Ryan’s words, an “experimental modernist” writer who has created an innovative novelistic aesthetic. For example, Faulkner’s radical novelistic aesthetics and technique are very noticeable when compared to Thomas Wolfe, another Southern writer beloved by the author of these lines. Thomas Wolfe is a great narrator, his novels flow like a long river, and the reader is swept away by its waters. However, Wolfe is far from being innovative. On the other hand, it is enough to read The Sound and the Fury to realize what a radical novelistic aesthetic and narrative technique Faulkner has created.

In The Sound and the Fury, Faulkner’s masterpiece, he describes the decline of the old plantation order, the disintegration of the plantation aristocracy, the Compson Family, and the birth of the modern South in a very original style and with a new technique. The three children of the Compson family each narrate the collapse of their families separately. The disillusioned, overly sensitive, intellectual Quentin, the ruthless and materialistic Jason, and the cognitively disabled Benjy. The episode told from the latter’s point of view is, in Tim A. Ryan’s words, ‘a modernist tour de force’.

Faulkner lived and wrote in a region and in a period of intense racism. His thoughts and feelings about race relations were in some ways no different from the average white Southerner, and he shared the same prejudices as his white neighbors. As a young man, he wrote a letter to the editor of a Mempshis newspaper in which he made scandalously disgraceful statements about lynch mobs administering justice like juries in a court of law. In an article he wrote for Life, he criticized the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), which aimed to end racism and achieve racial equality, and especially Brown v. Brown.

He drew parallels between the Citizen’s Councils, organized by white supremacists unhappy with the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Board of Education Case that it was unconstitutional for blacks not to be educated in the same schools as whites. In his later years, as he gained fame as a writer, he was more cautious in his public statements and writings on race, which were often far from clear, complex and confusing.

In the summer of 1955 in Mississippi, a fourteen-year-old black boy named Emmett Till was accused of molesting a woman and lynched. An all-white jury found those who brutally murdered the boy not guilty. Faulkner, the South’s most famous writer, wrote an open letter two weeks after Emmett Till’s body was found. He asked whether the white race, only a quarter of humanity, could survive by continuing to commit crimes against blacks. He also argued that Till’s murder belied America’s Cold War rhetoric of freedom and justice, and that claims that America represented the liberal side could no longer be credible.

Nine months later, in the June 1956 issue of Harper’s Magazine, Faulkner returned to the Till case, this time focusing on ‘fear’. In the case, two armed adults kidnapped a fourteen-year-old black boy at night. The boy, alone, unarmed and unprotected, was not afraid, but the armed adults who had kidnapped him were afraid and destroyed him. Faulkner also told a radio reporter, “What I experienced in the South was not hate, but fear.” He saw fear, not hate, at the root of racism.

The early 1950s saw the rise of the civil rights movement, which had a profound impact on the South. Politicians and the white activists who supported the movement were seriously committed to solving the race problem. Faulkner was a respected writer at the time, having won the Nobel and Pulitzer prizes. What he had to say about the race question and civil rights was important and would be influential. As a Southern intellectual, he never openly supported the civil rights movement. He urged restraint on the part of activists, favoring moderation and slow progress. In essence, he was voicing his own concerns; after all, he was a white Southerner worried about the rise of the civil rights movement.

The land where Faulkner was born and grew up, Mississippi and its environs, has been seen as a ‘cultural wasteland’. This is true if you ignore, disregard and deny the existence of black culture. However, there is a deep-rooted black tradition that enriches the geography in question; this cultural tradition manifests itself most intensely and effectively in music, especially in the blues.

Tim A. Ryan compares blues musicians to the world’s oldest storytellers, describing them as the ‘Homers of the cotton fields’. An interesting analogy, but incomplete. In the South, the blues was not only in the cotton fields, it was everywhere and in every moment of everyday life. In secluded places on the banks of the Mississippi, in cabins, train stations, barber shops, at the crossroads in the countryside, on the corners of deserted towns… Blues was the “heartbeat” of the South.

The blues was a tragic music that expressed the suffering of black people, referencing the white violence and Jim Crow terror they were subjected to almost every day. In his book Seems Like Murder Here, scholar and blues harmonica musician Adam Gussow argues that the blues was often a coded response to white violence and its ultimate form, lynching. According to Gussow, blacks resisted violence with the blues, this music strengthened their spirits and kept fear at bay. It was the music of the hard times they lived through, of the dramatic moments in their lives. Blacks were speaking in the blues, voicing their anguish and objections in the blues.

Faulkner shared many of the racial prejudices of white Southerners, but he loved black music, especially the blues, and felt that it enriched the culture of the South. Moreover, the blues influenced his novels and stories. “The Evening Sun” is a story in which blues music is heavily influenced in several ways. He used blues narratives to create the black characters, develop the plot and build the dramatic structure.

Some of Faulkner’s novels and stories can be considered examples of a kind of Southern gothic, an uncanny literature unique to the South. His stories and novels are haunted by the ghosts of black people whose bodies were mutilated, burned, hung from trees, and thrown into the river by white racist mobs and lynch mobs. During the Jim Crow era, black bodies dangled from trees and telegraph poles; they were dismembered, burned, hanged. In the geography where Faulkner grew up, lynching was a horrifying public sport. A sport played by whites, watched by whites.

Lynchings are among Faulkner’s unforgettable childhood memories. The horror of lynching remained vivid in his memory. That is why the black victims of racist violence return in his novels and stories. In 1908, in Oxford, a black man, Nelson Patten, a moonshine maker accused of murdering a white woman in the town square not far from their home, was imprisoned, only to be taken away by a lynch mob and hanged from a pole in the town square. Faulkner was eleven years old when this happened. He never forgot that night of terror in the town. He was not a direct witness, but the sounds of the lynch mob storming the jail and gathering in the town square could be heard from his house. Even those sounds were enough to frighten and terrify him. The ghost of Nelson Patton always came back to him, bringing with him laments for the lynched blacks; he came out with blues music.

“The Evening Sun” is said to be based on this event. First published in the American Mercury in 1931 and appearing in anthologies many times in the following years, the story takes its title from the first line of W.C. Handy’s very popular composition ‘St. Louis Blues’: “God, I hate to see the evening sun go down”.

W.C Hardy’s blues-style composition is the story of a woman who is abandoned by her husband. She complains of a man who is hard, cruel, with a ‘heart like a rock’. Every sunset she remembers her lover. Her pain, longing and loneliness intensify as the sun sets in the evening. In Faulkner’s story, Nancy, the black laundress, is terrified as the sun sets. She is expecting a child, but her lover Jesus has left the house where they live together, suspecting that she is pregnant by a white man. Nancy is afraid that Jesus will return to kill her.

The story is connected to The Sound and the Fury in several ways. First of all, the narrator, Quentin Compson, is no stranger to Faulkner readers. In The Sound and the Fury, this highly sensitive, introverted, neurotic son of the Compson family had committed suicide at the age of twenty when he went to Boston to study at Harvard and ended up in the waters of the Charles River. Faulkner gives his unforgettable character Quentin Compson another chance to tell Nancy’s tragic story; he brings her back to life, but this time at the age of twenty-four. Unlike his brothers, Quentin is aware of the dangers that await the black washerwoman in the outside world and understands her worries and fears.

Translated from Turkish to English Sources: HALİL TURHANLI