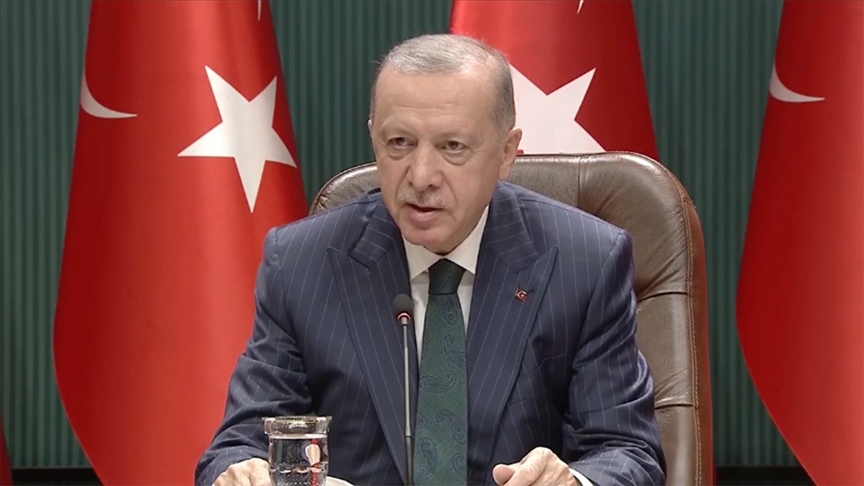

Even if observers in the West, who have been frustrated by the Turkish president for years, do not want to admit it: Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is currently enjoying one prestigious success after another on the international stage. Still shunned by many partners at the beginning of the year because of his erratic changes of direction, heads of state and government are now seeking his proximity – both politically and geographically. The first Ukrainian-Russian meeting at ministerial level after the start of the Russian attack took place in Antalya, later negotiations between the warring parties in Istanbul.

The EU, Ukraine and Russia praised Turkey’s policy of balancing the war and its commitment to regulating Bosphorus shipping in accordance with international law. In the context of Sweden’s and Finland’s NATO accession negotiations, Erdoğan wrested important concessions for him from the Scandinavians and was able to produce prestigious pictures with U.S. President Joe Biden along the way. And most recently, Russia and Ukraine, under the personal mediation of UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres in Istanbul, agreed to establish a corridor through the Black Sea to export Ukrainian wheat, which is urgently needed worldwide. Guterres, like the U.S. State Department a short time later, expressly praised Turkey’s constructive role.

- WATCH: Days before the second positive test, Biden pokes fun at Trump over COVID-19

- In these recent throwback images, The Kardashian-Jenners are all essentially unrecognisable from now

- 22-year-old man arrested over the murder of nine-year-old Lillia Valutyte

The fact that Turkey is currently able to make such a name for itself is no coincidence. It is an expression of tectonic shifts in the international balance of power, a geostrategic turning point. Never before has Turkey’s importance been so great as it has been since the beginning of the Russian attack on Ukraine. Its traditional southeastern flank is now stronger than before NATO’s Black Sea counterweight to Russia. Moreover, Turkey is perceived as a force of order and a bridging power with contacts to all relevant actors in the region. Knowing Turkey as a partner in the reconfiguring world order is currently more important than the problems of the past, even if these have by no means been solved. Whether it is the steadily deteriorating situation of the rule of law, restrictions on media freedom and freedom of expression, or differences on individual foreign policy issues, relativizing problems and including Turkey are clearly more in vogue than exhortations at the moment.

President Erdoğan knows this and is playing his hand in international forums more than ever to get what he wants. Turkey’s revaluation must seem like a godsend to him to escape a seemingly unstoppable vortex. For in view of a disastrous economic situation, he faces the threat of losing power in the presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for early summer next year at the latest. For months now, a campaign has been underway to focus the population’s attention on foreign and security policy.

But even in this area, not everything is going as well as his prestigious successes would lead one to expect. Erdoğan experienced a severe setback last week in Tehran. It was a peculiar summit meeting that was staged there before the eyes of the world public. Media and international observers followed the meeting of the so-called Astana Process, which has been gathering selected parties to the conflict in the Syrian war since 2017, with great attention. For Russian President Vladimir Putin, this was the first trip to a country outside the territory of the former Soviet Union since the beginning of the attack on Ukraine that he ordered. For many observers, the fact that the Russian pariah chose Iran, of all countries, isolated internationally by strict sanctions, for this trip was an expression of Russia’s new, unflattering standing in the global community.

The focus on the two autocrats Putin and the Iranian host, President Ebrahim Raisi, at first almost relegated the third participant in the meeting to the background. Yet, with Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, an important ally of Ukraine, not only did he come to Tehran, but also the highest representative of the second strongest NATO member in terms of troops. At a time when Russia is being isolated by Western states at great expense and negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program are on the verge of collapse, Erdoğan produced images of global scope with the declared enemies of the West. Many in the EU and NATO asked anxiously what Erdoğan, perceived as an insecure cantonist, was trying to achieve with his foreign policy behavior. A closer look, however, reveals familiar patterns – and rather little cause for concern.

Viewed soberly, Erdoğan pursued three goals with his visit. In typical Turkish fashion, the visit to Tehran was intended to signal to Western partners the strategic ambiguity of Turkish foreign policy. Systematically, the president evaded capture by either side. Just a few weeks ago, there was great relief when Turkey relented and gave up its opposition to Sweden and Finland joining NATO. NATO circles said that the Turkish president’s maneuvering for power had been won over by the responsibility of state policy. The fact that the highest representative of the Turkish state is now meeting with NATO’s declared main enemies immediately afterwards is in line with Erdoğan’s principle of always having several foreign policy footholds. Beyond images intended to show demonstrative unity, however, it was mainly differences that came to light. It became abundantly clear to all observers, including the three leaders, that the alliance is on shaky ground.

Internally, according to the second objective, the visit is a piece of the puzzle in an image campaign that has been underway since the start of the Ukraine war and presents Erdoğan on a par with the world’s most important state leaders. Already his statesmanlike photos with U.S. President Biden during the NATO summit in Madrid complemented Erdoğan’s images as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine. The fact that Erdoğan now shows himself in grand gestures with Raisi and Putin completes his image in the Turkish media. It not only highlights his weight on the international stage, but also appeases the numerous voices critical of NATO among the Turkish population and those of his coalition partner, the radical nationalist MHP.

Finally, Erdoğan is emphatically pursuing a very concrete, power-political goal. For months, he has been talking about the need to conduct a large-scale military operation in northern Syria to crack down on the PKK-affiliated YPG militia. The result, in addition to fighting Kurdish separatists, is supposed to be the establishment of a Turkish-controlled border strip to which a considerable number of Syrian refugees can subsequently be repatriated from Turkey. Turkish units have already repeatedly flown attacks on YPG positions on Syrian soil in recent weeks, but this is not yet enough for the president. For a large-scale attack on the Kurdish areas of Syria, however, Erdoğan needs the placet of the Assad regime’s two protectors, Russia and Iran.

Here, however, he failed across the board. Putin and Raisi gave Erdoğan a complete run for his money beyond a general endorsement of the principle of fighting terrorist organizations. Both stressed the importance of Syria’s territorial integrity and issued a clear rejection of any invasion plans by Turkey. Turkey, it should have become painfully clear to Erdoğan, does not hold the same levers of power with Russia and Iran as it does with the EU and NATO. “Turkey cannot offer Iran anything that would make it change its position,” says Ilhan Uzgel, an expert on Turkish foreign policy. “On the contrary, Iran is already unhappy with Turkish influence in neighboring Iraq, which Iran perceives as competition to its own hegemony.”

A July 20 attack on the northern Iraqi town of Zakho that left nine dead, for which Iraq blames the Turkish military, may have further hardened the battle lines in this regard. “Russia, after all, at least has an interest in Turkey continuing in a mediating role in the Ukraine war and not going along with the West’s tough sanctions course,” Uzgel continued. “With Russia, Turkey can negotiate. But apparently Moscow is convinced that it doesn’t need to sacrifice control over Syria in such negotiations.”

For Erdoğan, this realization is a setback. Many observers are convinced that a military operation in the Syrian Kurdish region was to become a central part of his election campaign. Fanning the flames of Turkish nationalism should thus bring about a shift in opinion and guarantee his reelection, despite record inflation and rising discontent. And this would be sorely needed: Almost all polling institutes currently see the opposition alliance led by the Republican CHP clearly ahead.

The only success Erdoğan was able to achieve in Tehran was that he made Putin wait 45 seconds for him in front of the cameras of the world public, independent media mocked. However, experience shows that one should never underestimate the Turkish president. Quite skillfully, he has positioned Turkey as a “hybrid partner country” of NATO, which is at the same time an ally and pursues an almost completely independent foreign policy. This position gives Erdoğan considerable foreign policy maneuvering room, which he will use in the coming months. Whether it’s Syria, Cyprus, Greece or Armenia: Turkey’s neighbors will have to watch closely to see what lessons Erdoğan learns from his failure in Tehran.

Original title of the article: Die neue geopolitische Ära spielt Erdoğan in die Hände. Doch dass die Bäume nicht in den Himmel wachsen, musste er schmerzhaft in Teheran erfahren.