Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was assassinated on July 8, was one of those who attempted to avoid acknowledging the fact that the Japanese used 200,000 women (some sources put the number at 400,000) as official sex slaves in Southeast Asian nations they occupied in the 1930s and 1940s to relieve their own soldiers.

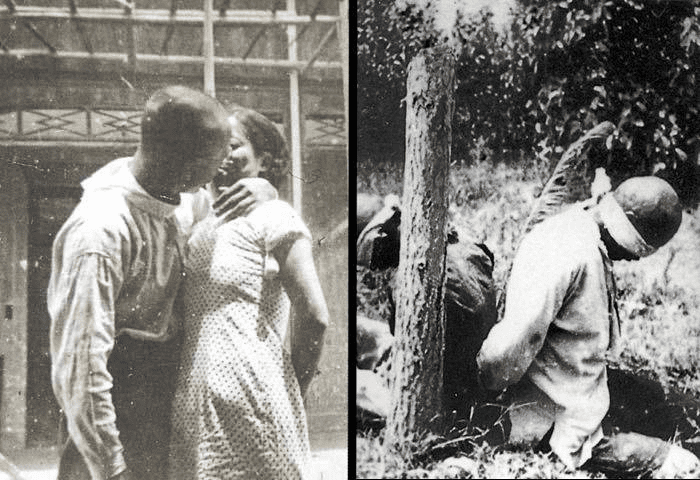

It is known that during those years, the Japanese employed them at facilities they formally referred to as “sexual relief businesses” and figuratively referred to as “public restrooms.” These ladies came from Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Timor, Macau, Taiwan, China, and Korea, among other nations.

Wikimedia Commons

Tokyo Courts

Because some of these poor ladies were tortured to death over those years, just 10% of them managed to live. Those who lived succumbed to the disgrace and perished young. Contrarily, sexual assault and rape were absolved at the Tokyo Tribunal, which tried Japan for its war crimes in the years following the Second World War (May 1948–October 1948), with relatively minor charges like “inhuman treatment,” “ill-treatment,” and “failure to protect the honor and dignity of the family.” Only the 14th Army’s commander, General Yamashita, received punishment for rapes committed while doing his official duties.

The tragedy was known thanks to the diaries of an American woman named Winnie Vautrin and a Nazi businessman named John Rabe, who worked in the area as the International Safe Zone Officer and played a kind of Oscar Schindler, rescuing many prisoners. Vautrin committed suicide in 1941. Rabe, who was expelled from the Nazi Party before the diaries came to light, died in poverty in 1950.

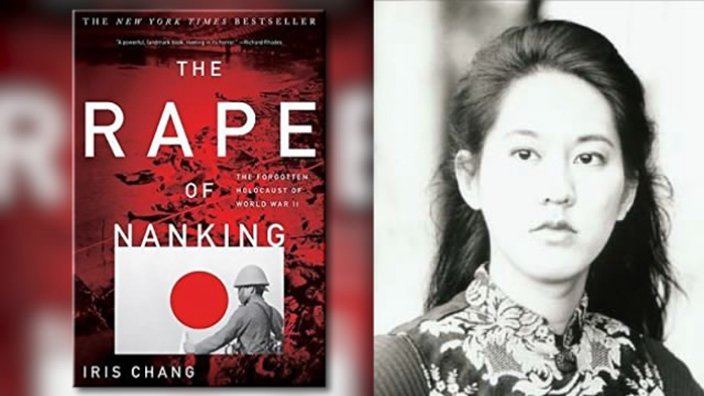

Iris Chang’s heartfelt book

I said “the incident was known”, but in fact it was not dwelled on much after that date. The book The Rape of Nanking by Chinese-American writer Iris Chang, published in 1997, broke this silence. The book, which not only talked about the Nanking massacre, which lasted six weeks from December 13, 1937 and claimed 300,000 lives, but also about the labor camps set up by the Japanese, the mistreatment of prisoners of war, and the biological and chemical weapons experiments, caused a great uproar at the time. But the real surprise was that such barbarity remained in the dark corners of history for 60 years.

Wikimedia Commons

Causes of reticence

While the West’s prolonged silence on Japan’s war crimes was attributed to the policy of “not offending Japan”, which was one of the West’s most important allies against Maoist China during the Cold War, China’s silence was explained by the fact that it was focused on being recognized by Japan in order to take its place on the world political stage and that economic relations with Japan were vital for China’s prosperity.

The theory of crime and shame societies

Could this shameful silence be explained by historical or political reasons alone? According to the anthropologist Ruth Benedict, who has a seminal approach to these issues, there could also be cultural reasons behind the difference in attitudes between Westerners and Japanese and Chinese.

Benedict roughly divides the societies of the world into “crime” and “shame” cultures. According to Benedict, “cultures of crime” are societies that are autonomous and respect human rights, independence, self-determination and freedom.

“For the member of these cultures,” Benedict says, “it is not the pressure of society that matters, but the inner voice of man, no matter how low that inner voice may be, he always hears it. If he has made a mistake, he says ‘I have sinned’, ‘I have done wrong’ and seeks forgiveness, without anyone warning him.” Benedict does not say it explicitly, but it is likely to be related to the Christian concept of “original sin”.

According to Benedict, in “cultures of shame”, judgments of right and wrong are determined by external factors. For example, for a Japanese person, personal autonomy, independence and freedom are more important than submission, loyalty, meeting the expectations of others, reciprocity, belonging and social responsibilities. Therefore, the person lives in fear of being rejected, ridiculed and shamed by the social environment. If the person has done something wrong, his only hope is that it will not be noticed by others. Thus, until someone condemns him, he continues to live ‘honorably’ despite his wrongdoing. When his wrongdoing is discovered, he commits harakiri.

Although some scholars later showed that it was not easy to make such precise distinctions between Eastern and Western societies, Benedict’s conceptualization was not completely invalidated.

Japan’s failed apology policies

Indeed, in 1998, a Japanese court rejected compensation for Chinese women on the grounds that “all women suffered during the war”. Eventually, through the efforts of both the victims’ countries and human rights organizations, Japan apologized, albeit half-heartedly. Finally, in 1994, Japan paid 800 million dollars in compensation to the Asian Women’s Foundation. Since then, however, many Japanese politicians and even historians have made statements that have mitigated and legitimized the tragedy (such as ‘the number did not exceed 10,000’ or ‘the women were all volunteers’).

Iris Chang, the author of The Rape of Nanking, shot herself on November 9, 2004, at the age of 36. In addition to having bipolar disorder, she had been subjected to harassment, exclusion, and insults by Japanese nationalists and militarists at all levels ever since 1997. Of course, the nationalists in the nations where these unlucky women were born condemned this frankness since it would undermine their “national pride.”

The author of The Rape of Nanking, Iris Chang, committed suicide with a pistol on November 9, 2004, at the age of 36, not only because she was bipolar, but also because she had been oppressed, ostracized and insulted by Japanese nationalists and militarists at all levels since 1997. Of course, the nationalists of these unfortunate women’s home countries also denounced this outspokenness because their “national pride” would be hurt.

Shinzo Abe was one of those “revisionist” politicians who favored the concealment of this bitter truth as much as possible. His stance on the issue has fluctuated greatly over the years: in 1993 he said “there is no evidence that these women were sexually abused”, in 2014 he joined the revisionist historian lobby Nippon Kaigi, which is said to have 35,000 members with 15 ministers, and in 2016 he announced that he had “no intention of issuing a letter of apology on this issue”.

Abe, who, in the words of one of my followers, “enacted discriminatory policies and insidiously crafted legislation during his tenure as prime minister with the aim of de facto enslavement and exploitation of foreigners in the country under the guise of fabricated laws, fabricated visas and a fabricated asylum process,” most notably tried to change Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution (added by the Allies in 1947), which prevents Japan from entering the war, but fortunately failed. This is how we know the deceased.

NOTE: This article was not written to justify the assassination of Shinzo Abe. His death is merely a pretext for linking the contemporary with the historical.

Ayşe Hür, Turkish investigative writer, historian and columnist.